4. From Global Market to Global Village

As early as the 1940s, several colonial agricultural experts had urged Kenya’s local administration to remove the regulatory mechanisms preventing black Kenyans from cultivating tea and coffee.[1] The outbreak of war in 1952 combined with Roger Swynnerton’s promotion in 1954 to the position of deputy director of agriculture in Kenya gave the necessary impetus to finally impose reforms leading to the creation of a class of black, cash-crop plantation owners. This class, in aligning its political and economic interests with white plantation owners, was intended to guarantee the security of the existing cash-crop system.[2] Collaboration between a black and white bourgeoisie would help safeguard colonial settlers’ land holdings and their subsequent access to a large pool of landless, underpaid agricultural laborers.

Within this expanding cash-crop economy, landowners required timely information about fluctuating crop prices on the global market, underscoring the close relationship between a “free market” and “free speech,” the latter including the untrammeled flow of economic information. A long-standing Anglo-American conflation of the market and the public sphere—of free trade and free speech—presented a dilemma, however, in the context of colonial martial law, villagization, and efforts to push Kenya more fully toward agrarian capitalism. The problem involved a question of media, as attested by McLuhan’s notion of “market society.” He claimed that the existence of “market society . . . required centuries of transformation by Gutenberg technology” and “presupposes a long period of psychic transformation” through literacy.[3] The Soviet-bloc nations failed, he said, to develop into a market society because their psychic apparatuses had not been adequately conditioned by typography.[4] If market society could only be inaugurated by a polity already liberated by the psycho-semiotic effects of print media, then the vast part of the world McLuhan described as subliterate (basically everywhere except North America and Western Europe) apparently would not belong to “market society” despite its increasing absorption in the global market. In the context of capitalist ideology, it is not difficult to see how McLuhan might attribute to market society the same cultural lineaments he ascribed to Gutenberg technologies, namely those of independent self-regulation. Since the global market was construed as self-regulating according to economic “nature,” implicitly market society would be constituted by intellectually self-regulating subjects; that is, subjects who, thanks to print technology, had been liberated from the enchantment of oral authority.

In Kenya the need for selective media connectivity—for connecting farmers to a global market without facilitating the free circulation of political expression—found expression in a particular architectural feature of villagization.

In a plan for “permanent villages” (i.e., those intended to remain even after demilitarization), Kenya’s chief health inspector, Harvey Waddicar, distributed 280 single-room houses around a large central area labeled as “market open space” surrounded by a ring of “shop plots.”[5] As the war had curtailed normal economic activity, Waddicar’s generous allotment of market space is striking. Colonial administrators frequently bemoaned the lack of land suitable for villagization (the war having been precipitated largely by land shortages).[6] And villagization had seriously disrupted agricultural production by conscripting detainees to work on infrastructural projects in lieu of cultivating food crops. Given reports of rampant malnutrition in the detainment camps, it seems there would have been little to buy or sell in the market Waddicar delineated.[7]

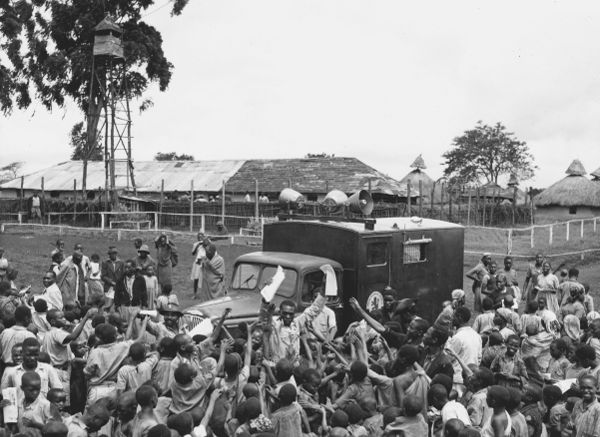

Figure 1. Van with radio broadcast and British news services in the “new village” of Kianjogu. The National Archives, TNA CO 1066 963/22.

The allocation of such a large market space appears overdetermined by two strains of colonial strategy: first, to mark the permanent villages as a microcosms of a future agrarian capitalist society (recalling that the direct inspiration for Kenya’s villagization came from Britain’s recent war against the Malayan Communist Party); and second, to reiterate—in colonial form—Britain’s conflation of a free market with a public sphere, albeit in this case, a public sphere violently evacuated of meaningful content. Photographs of Kenya’s detainment camps show how these central areas functioned as sites of media reception for colonial psychological operations (“Psy-Ops”).[8] Vans outfitted with radio broadcasting speakers parked there, disseminating various forms of propaganda to the gathering crowds of detainees. To designate this central space a market (one devoid of actual commerce but suffused with broadcast media) indicates the subjugation a two paradigms of exchange (commerce and discourse) with two paradigms of consumption (welfare rations and broadcast media).

McLuhan, who had explored the workings of advertising media in his first major book, The Mechanical Bride, was interested in how media governed not through their explicit content but through the cognitive environments they produced. In Gutenberg Galaxy, following his protracted citation of Carothers’s theories, McLuhan turned to research on Britain’s Colonial Film Unit in Africa to understand the effects of film on African psychology.[9] One finding of the Colonial Film Unit was, unsurprisingly, that educational films were less compelling to audiences than films intended purely as entertainment, suggesting that the latter might therefore serve as a better instrument of soft power.[10] Another observation made by researchers at the Colonial Film Unit—anticipating McLuhan’s theories—was that ultimately “the content” of the medium was far less important than the cognitive habits and preferences the audience brought to bear upon their reception of the film in question.[11]

In the Colonial Film Unit’s discussions, as well as in McLuhan’s work, a specific idea of nootechnologies emerged, one that located the power of those technologies not in the explicit content they purveyed so much as in the magical sway they held over audiences. Media did not alter minds only by implanting didactic instruction and Anglophilic imagery (the typical content of British colonial films); it altered them simply by what it was. As such, the “market open space” in Waddicar’s plan seems to have offered a resolution to the colony’s vexed predicament of how to instate a free market while discouraging the political agitation associated with free speech. The resolution is the transformation of the public sphere from a site of discourse into a site of media reception.