Learn and Work While You Sleep

Science and Invention, vol. 9, no. 8, December 1921

The normal human life covers a period of some seventy years. During this time, the average adult sleeps eight hours a day, or roughly speaking, one-third of the time. But, the individual when he reaches seventy years of age may be said to have lived only about forty-five years. The other twenty-five years have been taken up in sleep.

While the average length of sleep is about eight hours, it must be taken into consideration, that up to the tenth year, the human body requires more than eight hours of sleep daily, and there are many days during the year, such as holidays, when we sleep considerably more than eight hours. This brings the average up to somewhere near our figures. In other words, over one-third of our lives may be said to be wasted by unproductive sleep. During this time, we are truly dead in the best sense of the word, because sleep is only another form of death.

During our sleeping periods all our usual functions are suspended; of our five senses none remain conscious. We hear no longer; we feel no longer; we see no longer; we smell no longer; we taste no longer. This statement may be qualified at once, by saying that all of the five senses have ceased operating only if conditions are right, or rather normal. To elucidate, a man may be sleeping soundly near a busy railroad, where trains crash along every few minutes, and he will not wake up. He has become accustomed to the disturbance. But let a rat or mouse start nibbling in a corner of his room, and he will wake up almost immediately. Why is this so? The reason is that the human body while asleep, is only dead to the accustomed things, and the instant something unusual occurs, the sentinels of the particular sense affected immediately send out its warning.

Thus, while we do not hear the ponderous trains crashing by, the unaccustomed noise of the nibbling mouse awakens us, because it was not foreseen by the sleeper. Our subconscious self never sleeps. It is always on the alert. All of the other senses act in the same way, as just exemplified with the sense of hearing.

Thus we sleep along peacefully, but an acrid odor, which is not foreseen, will awaken us. We may turn around and toss about in bed and have every part of our body come in contact with the linen of the bed. It will not awaken us, but a single drop of cold water falling on our hand, will instantly rouse us. Why? Because it was not expected by the sleeper. The same is the case with taste. A man may be snoring along peacefully with his mouth wide open, but if you allow a few drops of sugar-water, or any other unusual solution to fall upon his tongue, he will awaken to nearly every case.

You might think that, when closing your eyes during the night, light would not affect the retina. This is far from true. Try the experiment of switching on an electric light close to a sleeper’s face. He will awake almost instantly. Why? Because the lids are translucent, and allow light to pass quite easily. The moment an unaccustomed strong light falls upon the eye lid, we awake.

Why do we not then awaken in the morning when the sun light falls into the room? Very simply because we have grown accustomed by many years of experience to this daily procedure, so it no longer disturbs us. It is the accustomed thing, that fails to disturb the subconscious self, but the unusual affects it strongly.

The writer found it necessary to digress from the real purpose of this article, simply to show how the human body acts under various stimuli.

Suppose we could find a way in which we could act upon our sleeping senses in the night time! We would immediately have lifted up the entire human race to a truly unimaginable extent.

Suppose it was possible for you to read, learn, or work while you sleep. Would we not thereby extend the period of our lives by one third?

Suppose it was possible to devise an apparatus whereby you could read a book or study a language while you slept. Would it not be an inestimable boon to humanity? We may be sure that in years to come, we will have arrived at just such a point. There is nothing impossible in science, and our problem is greatly simplified by the fact that when the body is at rest, it is most easily influenced, and impressions are retained best. For instance, when we sit at rest, totally relaxed, and view the latest motion pictures, it makes a lasting impression upon us, because our mind is not diverted by anything else. If we dream a vivid dream during the night, or better during the early morning, a lasting impression remains depending greatly upon the intensity of the dream, and it must be remembered that a dream is only the most fleeting thing that can be imagined. There is no outside impression upon the brain. It is only a picture. That is why we do not remember mere thoughts so well. For that reason, most people when they have an idea, find it necessary to write it down, as a thought itself makes practically no lasting impression.

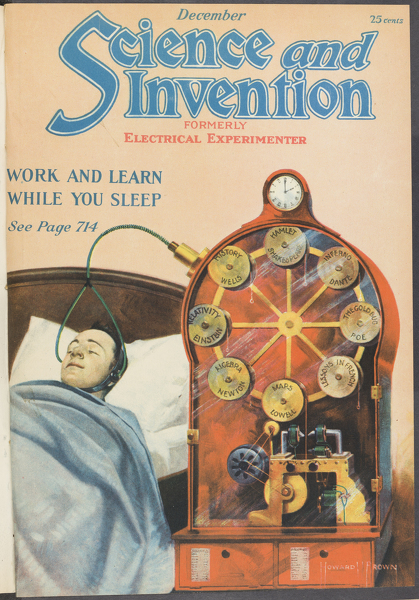

Suppose we were to build a phonographic machine, the sound of which could be conveyed to the ear by two rubber tubes as shown on the front cover of this magazine. Suppose also the music was not grating upon the nerves. What would happen? At the first attempt the sleeper probably would wake up startled because he was not accustomed to it. It probably would take a week before he could accustom himself to wear a head-gear attached to his head by means of a heavy rubber band, and before he could submit to the annoyance of it as well.

After he became accustomed to the head-gear as well as to the unfamiliar noises, it is very probable that his subconscious self would take note of what was going on while he slept. Thus, were it music, or the spoken voice, it seems almost certain that in time, a lasting impression would be made upon the brain through the auditory nerves.

It would be a matter of education. Probably for the first few months, not much impression would be made upon the subconscious self, but by-and-by the hearing sense would be sharpened to such an extent, that the impression would not only reach the brain center, but would be so permanent that the hearer getting up in the morning, would remember something of the nightly procedure. It is remarkable to how many things the human body would respond. It is equally remarkable how many new things the human body is able to absorb. Reading and Writing for instance 300 years ago were considered a science. To-day every school child has absorbed them, and reads and writes unconsciously.

Every time you use a typewriter you write absolutely unconsciously or rather automatically. The expert typist does not have to stop to think of each key when writing. It is done automatically and she pays not the slightest attention to the keyboard while writing. It is a habit formed by the long experience. It may be that the same thing will be true of subconscious learning while you sleep. Once the human system has accustomed itself to the various impressions, there is no doubt that in the morning we will remember everything that we hear during the night. It may take several generations before such a system will be perfected, because human nature would have to accustom itself slowly to the change. In our front illustration, we have tried to show in a practical way the modus operandi, and how it can be accomplished.

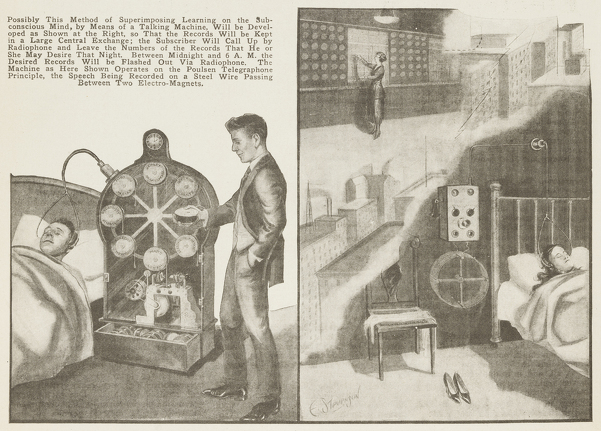

An ordinary phonograph would, of course, not do. There would be too many grating, jarring noises, which would distract the sleeper’s attention. We must have a mechanism that is soft in action, gives no extraneous noises, and will not wake up the sleeper. We have such an apparatus in existence today—the telegraphone.

Its action is based on a steel wire, which is fed across and very near to the poles of an electro-magnet; the magnet is polarized by currents derived from a telephone, and the wire is polarized thereby in an almost infinite number of exactly corresponding poles. On moving the same wire in front of the same or another magnet, the induced telephonic currents are made to act on a transmitter. The telephone receiver has the message repeated in it from the transmitter, without any grating or jarring noise.

By means of a loud talking or amplifying arrangement seen at the upper or left end of the cabinet, the voice, or sound may be amplified to a loud enough degree so that it will give a lasting impression to the sleeper.

The machine which we depict upon our cover contains a number of reels, each of which has enough wire to last for about one hour continuous service. Each reel comes into position automatically as soon as it is “played”; thus eight reels will give the sleeper enough material for a whole night’s work.

Whether he wishes to be entertained, or whether he wishes to learn, depends upon himself. It probably would not do to learn history for eight hours at a stretch, for the mind probably would not absorb it all. So we might switch from history to romance, then we might have a concert for an hour to get accustomed to the music of the latest opera, then switch back to mathematics if necessary, and arrange the program as we may see fit, and so as to suit our own individual taste.

Learning, which is remembering, is like any other practice. Some people can remember the contents of a book when only read once. It takes others two or three readings to remember it well. For that reason if the “sleep-reader” thinks that not enough impression has been made by one reading, of any subject, there is no difficulty in repeating it the next night, or as many nights as he desires, until he has absorbed that particular matter.

All of the above is merely theoretical, of course, no machine having been tried but the writer would not be surprised to see one built and in operation in the not distant future.