Predicting Future Inventions

Science and Invention, vol. 11, no. 4, August 1923

Every inventor must be a prophet.[1] If he were not, he could not think up inventions that will only exist in the future. For this reason, every inventor must ascend from fact to non-fact. What non-fact will turn out to be, not even the inventor knows beforehand. He prophesies to himself that he can make such and such an invention, all the while thinking about it, and letting his imagination work overtime. He keeps on turning the question or problem over and over in his mind until the subject finally crystallizes itself into a concrete form. All of this takes place in the inventor’s mind. He is not working with concrete facts but he imagines and hopes that the particular device upon which he is laboring will turn out to be as he imagines it.

If the inventor’s imaginings were wrong, he is a poor inventor. If they are right, he is a good one.[2]

The art of inventing is to produce something that has not existed or has not been known on earth previously. Of necessity, therefore, it lies in the future. Sometimes an inventor may have a perfectly good idea of a certain machine, which he is convinced will work, if certain conditions were fulfilled. He starts working it out until he finds to his dismay that he cannot produce certain materials or certain articles which he knows are needed, but which have not as yet been developed. For instance; inventors over 150 years back, knew the automobile. Steam automobiles operated on the roads of England in the 18th century capable of running at a fair rate of speed and could carry from ten to fifteen people. Such automobiles failed because the automotive power had not as yet been developed perfectly. The missing link was the gasoline engine, which up to that time was not known. The inventor had had all this in his mind’s eye and he was prophetic enough to realize that some day such vehicles would become commonplace, as indeed they are now. Jules Verne in his prophetic books, describes dozens of future inventions, nearly all of which have become realities. Indeed, there are not more than three or four of his imaginations left, and these no doubt will become true very shortly. Consider the submarine which was prophesied in its entirety by Jules Verne long before it made its appearance. He had laid the basis for the present day submarine, and lived to see the day when the first one was actually built and had operated as he had prophesied it would.

There are a certain class of people, and we hear continually from them, who condemn the policy of this magazine because we exploit the future. These good people never realize that there can be no progress without prediction. It is impossible to have in mind an invention without planning it beforehand, and no matter how fantastic and impossible the device may appear, there is no telling when it will attain reality in the future. To illustrate: in the August, 1918 issue of the Electrical Experimenter, the writer ran a story entitled: “The Magnetic Storm.” This was during the war and was a purely fantastic idea: the suggestion was made to stop the war by burning out all electrical instruments throughout Germany. The idea was to have a tremendously large Tesla coil along the border, which would send a current into all electrical circuits through Germany, burning out armatures, automobile wiring, electric installations of airplanes, telegraph and telephone apparatus, etc. While theoretically possible, the idea was very fantastic. Cable dispatches during the middle part of June of the present year brought the news from Germany that the very thing had actually been accomplished by the powerful Nauen radio station. A number of automobiles were stopped at a distance by the energy sent out from this station.[3]

Then again in this magazine we have for the last ten years exploited television, the faculty of seeing at a distance. We have shown all sorts of television schemes, all of which seemed to belong to the distant future. We have on file a great many letters from critics denouncing us for printing such “foolishness,” as they call it, because they said it would ever be impossible to invent a machine, by which a man could see at a distance. During the latter part of June, Mr. Jenkins of Washington, publicly demonstrated before Army and Navy officials a machine, whereby it is possible not only to see at a distance but to project a film on a screen in New York and broadcast it all over the country by radio the same as voice and music is broadcast by radio now.[4]

These are just a few examples among many.

And so it goes. What seems impossible and even ridiculous today becomes an actuality tomorrow. Throughout the ages, the man who looked into the future was usually considered a crank or insane. He is in the same population today. Human nature is such that it opposes changes, particularly if such changes are violent. Anything that tends to pull us out from our daily rut is not welcome, because it means an effort.

When some of our greatest scientific authorities, as late as twenty years ago, proved by mathematics that it was impossible to sustain in the air a machine such as an airplane; when the news of the X-ray was greeted with derision; when the sending of messages by radio was not believed by the populace, when it had already been used for years—it behooves the average man to be extremely cautious in denouncing any idea just because it is new and appears impossible on the face of it.

Notes

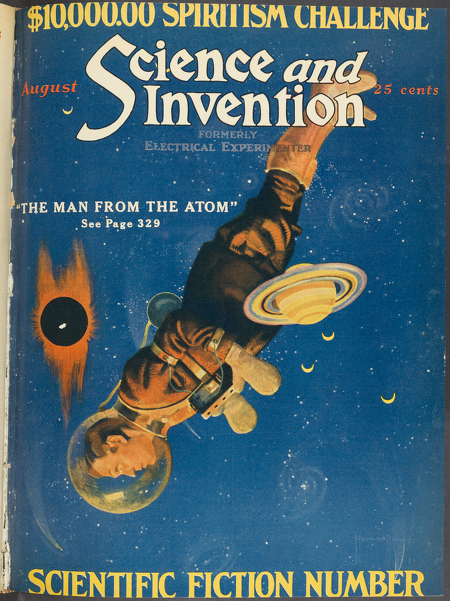

1. This editorial appeared in the special “Scientific Fiction Number” of Science and Invention, which featured six short stories in addition to the normal features, departments, and readers’ letters. The issue served as a blueprint for the launch of Amazing Stories in 1926. The cover image of an astronaut floating through space illustrates a story by the sixteen-year-old G. Peyton Wertenbaker, who in the words of Mike Ashley, “was Gernsback’s first important writing discovery. . . . His story is emotionally strong and considers the fate of an explorer who travels through into the macrocosm only to discover he cannot return to Earth because, with time relative to mass, the Earth had grown old and died within minutes of his own subjective time.” Michael Ashley, The Time Machines: The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the Beginning to 1950, The History of the Science-Fiction Magazine, vol. 1 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2000), 47.

The issue also included the nineteenth of the forty-installment Doctor Hackensaw series by Clement Fezandié (1865–1959), who Gernsback later referred to as a “titan of science fiction.” Hugo Gernsback, “Guest Editorial,” Amazing Stories 35, no. 4 (April 1961): 5–7, 93. Like Luis Senarens (see An American Jules Verne in this book), Fezandié was another late nineteenth-century author of dime novel scientific tales whose name Gernsback attempted to elevate to the level of Verne, Wells, and Poe within the canon of scientifiction. Fezandié wrote new fiction for Gernsback up until 1926. Each of his Hackensaw stories consisted of a technical description of a new invention by the rogue scientist Doctor Hackensaw and its possibilities, both in terms of practice and profit. Mike Ashley writes on Gernsback’s description of Fezandié as a “titan”: “That is hard to grasp by today’s definition of science fiction, but we have to remember that Gernsback was talking about his own definition. These stories more than any others in Science and Invention epitomized Gernsback’s model for scientific fiction. They extrapolated from existing known science to suggest future inventions and what they might achieve; and all for the sole purpose of stimulating the ordinary person with a penchant for experimenting with gadgets, into creating the future.” Ashley, The Time Machines, 34.

According to Sam Moskowitz, the reason for this special issue was “the backlog of science fiction stories piling up at Science and Invention, but it quickly persuaded Argosy and Weird Tales to alter their policies to include stories with a better grounding in science. The beginning of the end for the scientific romance which had been popularized by Edgar Rice Burroughs was brought nearer; the pattern of modern science fiction was in the process of formation. Except for a freakish circumstance, Gernsback would have issued the first science fiction magazine in 1924. That year he sent out 25,000 circulars soliciting subscriptions for a new type of magazine, based on the stories of Verne, Wells, and Poe, to be titled Scientifiction. The subscription reaction was so cool that Gernsback did nothing further for another two years, at which time he placed Amazing Stories, fully developed, on the stands without a word of notice.” Sam Moskowitz, Explorers of the Infinite: The Shapers of Science Fiction (New York: The World Publishing Company, 1963), 236.

2. Invention as a form of prophecy became a favorite topic of Gernsback’s Science and Invention editorials during this period. Distinguishing between the discovery and the invention of a new technical object in “The Mentality of Inventors,” for instance, he writes: “An inventor is an individual who rarely makes any discoveries himself. Rather, he takes up something that some discoverer has worked on before, and then makes it practical, which is something which the discoverer never does. For instance, Heinrich Hertz, the inventor of wireless, who was the first to demonstrate what we now term ‘radio waves,’ was a discoverer. And while he knew, perhaps, more about radio than most of us do today, he did not find or try to find a practical use for it, until Marconi, the inventor, came along, and not only put Hertz’s discovery into practical use, but commercialized it as well.” Hugo Gernsback, “The Mentality of Inventors,” Science and Invention 13, no. 7 (November 1925): 603.

Gernsback was also aware that this “mentality” of the inventor, namely the ability to sense future opportunities for innovation, was becoming something of a science among the various new wings of large corporations. “There certainly is nothing new about this, because it has been done for ages, but only in a haphazard manner. Everybody who had a little imagination could take a fling at predicting, and quite often the prediction came true. Your scientific investigator of today, however, tackles the problem in a thorough and often in a mathematical manner, totally different from the guessing predictions that were in vogue heretofore. The largest industrial corporations the world over have people on their staff whose business it is to predict certain inventions or discoveries having to do with their own business. And in nearly all cases, predictions thus made by staff scientists are realized usually within the space of time indicated by these modern prophets. . . . It is all well planned out mathematically, from data available at present.” Hugo Gernsback, “Predicting Inventions,” Science and Invention 13, no. 2 (June 1925): 113.

3. In a piece on two British aviators who disappeared “upon an ordinary reconnaissance over a desert in Mesopotamia” in 1924, the famous writer on occult and paranormal phenomena Charles Fort (1874–1932) attempted to follow up reports that German engineers had been experimenting with “secret rays” capable of arresting the movement of large objects. “It was said that for some time, at the German wireless station at Nauen, there had been experiments upon directional wireless, with the object of sending out rays, concentrated along a certain path, as the beams of a search-light are directed. The authorities at Nauen denied that they had knowledge of anything that could have affected the French aeroplanes, in ways reported, or supposed. Automobiles can be stopped, by wireless control, if they be provided with special magnetos. Otherwise not. Sir Oliver Lodge was quoted, by the Daily Mail, as saying that he knew of no rays that could stop a motor, unless specially equipped. Professor A. M. Low’s opinion was that he knew of laboratory experiments in which, over a distance of two feet, rays of sufficient power to melt a small coil of wire had been transmitted. But as to the reported ‘accidents’ in Germany, Prof. Low said: ‘There is a wide difference between transmitting such a power over a distance of a foot or two, and a distance of one or two thousand yards.’” Charles Fort, The Complete Books of Charles Fort (New York: Dover Publications, 1974), 955–56.

But the idea Gernsback put forward in The Magnetic Storm had definite legs, with stories abounding over the next decade on German experiments with secret rays. For instance, the New York Times reported in 1930 that Reichswehr officials denied that what “has been causing automobiles to stall mysteriously on a Saxon road near Czechoslovakia” had anything to do with “a secret ray cast across the unsuspecting countryside during government experiments. . . . And even if they were, it was added, they would be conducted in some isolated region and not on a public highway near the Czechoslovakian frontier.” “deny using invisible ray: Reich Army Officials Comment on Mysterious Auto Trouble,” New York Times, October 25, 1930.

Though he was convinced the phenomenon existed, Fort disagreed with Gernsback’s hope that any such ray could serve as a deterrent to war: “I am unable to conceive that a power to pick planes out of the sky would be so terrible as to stop war, because up comes the notion that counter-operations would pick the pickers. If we could have new abominations, so unmistakably abominable as to hush the lubricators, who plan murder to stop slaughter—but that is only dreamery, here in our existence of the hyphen, which is the symbol of hypocrisy” (957).

At the very edges of what Gernsback would consider to be true scientifiction, Fort’s influence on science fiction writers was “incalculable,” according to Damon Knight, the SF author, editor, and historian, who wrote an autobiography of Fort with a preface by R. Buckminster Fuller. “He had twenty-five thousand notes, in pigeonholes that covered a wall; they were not what he wanted, and he destroyed them. He accumulated forty thousand more. Eventually he began to see an unsuspected pattern in them. . . . In four books, The Book of the Damned, New Lands, Lo!, and Wild Talents, he assembled more than twelve hundred documented reports of happenings which orthodox science could not explain.” Damon Knight, Charles Fort: Prophet of the Unexplained (London: Littlehampton Book Services Ltd., 1971), 2–3.

Although Gernsback attempted to distance his publications in the 1920s from Fortean obsessions with mysticism and the paranormal, writing several editorials condemning “spiritism” in Science and Invention, he did file a “dummy magazine” with the U.S. Patent Office in 1934 with the title True Supernatural Stories, containing fiction by Clark Ashton Smith and H. P. Lovecraft. Sam Moskowitz, “The Gernsback Magazines No One Knows,” Riverside Quarterly 4 (March 1971): 272–74.

4. Charles Francis Jenkins publicly demonstrated his prototype of a mechanical scanning television system with synchronized sound and image on June 13, 1925. The terms he used to describe the image thus transmitted included “radio movies,” “radiovision,” and “shadowgraph.” For more, see Donald Godfrey, C. Francis Jenkins, Pioneer of Film and Television (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2014).