New Radio “Things” Wanted

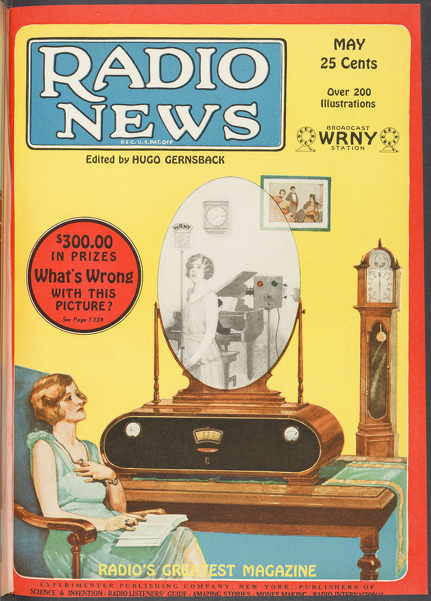

Radio News, vol. 8, no. 11, May 1927

. . . In which the Editor comments on the present tendency in radio circles to follow the well-known Calf Path—and suggests a few profitable lines for future experiment—what the Super-Regenerator promises—the need for truly portable sets—and the desirability of commercial apparatus to make them practicable—new tubes, new condensers, new coils—and finally adds a practicable “wrinkle” of his own invention—the “Cane Loop,” which makes a most compact and portable antenna for any set . . .

The progress of radio has been rather slow during the past two years. From the experimenter’s standpoint there have been few really new things to occupy him. There have been no revolutionary circuits, nor, as a matter of fact, do we expect them. Radio progress during the past two years may be said to have been refinement and improvement of what we already had. But there are many things still to be worked out, and a great deal of progress, as a matter of fact, the greatest progress, is as yet to come. The trouble with most of us is that we follow the well-beaten path, and as a rule we follow the leader. Very few experimenters and designers have the courage to step out from well-worn radio paths, because, as a rule, they are afraid that the results of their labors will be called freaks or worse.

A condition of this kind, of course, does not worry the progressive man, who, many times, has seen the very thing that was condemned come into favor and acclaimed in the end. When, in 1908, for instance, I published the first book on radiotelephony, entitled “The Wireless Telephone,” there was no such thing as a radiophone, because we did not then have the necessary vacuum tube. I described minutely many systems for accomplishing the thing, and I was laughed at by the press and others for my pains, but nevertheless it all came about practically along the lines I had predicted.

When, in 1921, I prophesied the single control, multi-tube radio set, it was said that such a thing was impossible of accomplishment, and the experimenters as well as the trade for years refused to work on such sets, but nevertheless they are an actuality today and will be the standard during the next two years.

The random thoughts which I set down here at this time may prove to be of a similar nature and time alone will tell whether the ideas are sound or not. Radio News, at my instigation, recently started a set-building contest along the Super-Regenerative lines. The Armstrong Super-Regenerator is one of the most wonderful circuits that we possess.[1] It is believed that in time this circuit will be the one that may yet prevail, because by means of it we can, with one or two tubes, accomplish the same thing that is done today with anywhere from 6 to 10 tubes. Unfortunately the circuit has never been perfected, due to its critical nature, but it is believed that sooner or later a solution will be found which will make this circuit come to the fore.

It certainly deserves this recognition. The Super-Regenerator is the ideal set for portable purposes, and where room is limited, all of this providing it is built so that it can be controlled. Here is a most fertile ground for research and for experimental work, and I suggest to experimenters that they busy themselves with this circuit. Perhaps some new combination will be found that will solve the problem.

Right here I wish to say that it is not always the new and revolutionary thing that is apt to become important. Sometimes an old and forgotten principle can be brought to the fore under new circumstances. For instance, the principle of the Marconi Radio Beam System of today was discovered by Heinrich Hertz in 1888. It was minutely described by him, but nothing much was done for some twenty years, until Marconi picked it up again and is now utilizing it.[2]

The same is the case with many other well-known radio principles, which may be found in text books, in magazines, and in the patent press. These things may have been obsolete ten, fifteen, or twenty years ago, but, due to later and newer developments of other apparatus, are of great importance today, or will be in the future.

At the present time there is need for the following new equipment: Experimenters and manufacturers need a new miniature vacuum tube. Such a radio tube, of the 199 type, should measure about ½-inch diameter by an inch to an inch and a quarter high, over all.[3] This would make it the smallest tube commercially available. It could be equipped with a bayonet socket to take up little more room than the diameter of the tube, and with such a tube it would be possible to make a small portable radio set the size of a box camera.

Radio News has already taken the initiative, and is urging tube manufacturers to bring out such a tube, which we hope they soon will. It is felt that miniature radio sets will be in great demand. There is no such thing as a convenient portable set on the market today. Most of the sets made are far too large and too heavy. With these small tubes it should be possible to build a set that does not weigh more than two or three pounds, and that can be slung around the shoulder like a camera, to be taken on long trips, for vacation purposes, and for general traveling.

Furthermore, small sets of this kind can be made for apartment dwellers, and wherever a small set is needed to be carried from one place to another. It may be said that, given such miniature vacuum tubes, we would still need small condensers. It is possible to make such condensers today, to make up a minimum of room, if such condensers are needed. It is known, for instance—a fact which has been forgotten for many years,—that by placing a variable condenser into castor oil, or some other high grade oil, the capacity of the condenser will be quintupled. In other words, by employing the oil immersion, we could make a 13-plate condenser one-fifth as large as we have at the present time for any given capacity. Furthermore, the equivalent of a 17-plate (.00035 mf.) condenser can be made by means of two metallic plates, separated by a sheet of mica. Of course the losses in such a condenser are comparatively high, but it is believed that these losses can be overcome by a greater efficiency elsewhere in the circuit.

It certainly is possible to turn out the equivalent of a 17-plate condenser in a space not larger than a paper book of matches. Inductances can be correspondingly small by means of the spider-web type of coil or even by means of a more efficient cylinder type of coils, wound with small wire such as No. 36 B. & S. gauge, enameled, it may be said that such coils also have losses, but we need not be concerned with this, because it is most likely that the set will have an oscillatory circuit, when it becomes necessary to kill oscillation anyway, and we might just as well have the losses in the coils or condensers as to get the losses by other “doctoring” means.

On the other hand, the future portable radio set, of the 5- or 6-tube variety, will probably not have any variable condensers at all. We may visualize the following system, which, to the best of my knowledge, has never been described so far. Imagine three small stationary spider-web coils. Then imagine three like coils mounted on a shaft, all to be parallel to each other. The three spider-web coils mounted on the rotating shaft swing back and forth approaching the stationary coils, or receding from them. The scheme may be likened mechanically to three variable condensers mounted on one shaft, except that instead of the plates we have six spider-web coils, three stationary, three rotatable. The tuning is then done by means of the rotating shaft. The six coils, of course, will be the radio-frequency transformers functioning as variometers. The stationary coils may be the secondaries, and the rotatable ones the primaries, or vice-versa. Such coils can be made very small, and need not be larger than about 2 inches in diameter. The thickness need not be more than one-eighth of an inch. Shielding may be applied between the various units, if this be necessary.

We have here, then, a condenserless set, which should be excellent for portable purposes, and where there is a minimum of room available. Having disposed of the small tube, the small condenser (which, after all, may not be needed), and the problem of small inductances, you may now rightly ask, “What becomes of the aerial and ground?” Here again there seems to be no difficulty. I have tried, with very good success, a device which I call the “Cane Loop,” and which was made up as follows: I wound rather heavy single-conductor lamp cord on a stick 1¼" in diameter by 33" long. This used up approximately 100 feet of wire. The “Cane Loop” can be used like any other loop, and is directive, as is the regular loop, and while it may not be quite as efficient, it still does the work nicely and brings in distant stations very well.

The “Cane Loop” can be used either horizontally or vertically. It may be laid on the floor or stood in a corner, or otherwise tucked out of the way. It has not quite the directive qualities of the square loop, which may be said to be a good thing, because it need not be rotated and turned, as does the usual loop. This, of course, makes it not quite so selective, but for purposes of portability, and where there is a minimum of room, it will prove ideal.

You will still say that such a loop is too big and can not be compressed into the space of a box camera. I already have an answer for this, as well. A collapsible and flexible “Cane Loop” may be constructed as follows: On a smooth broom handle start to wind 100 feet of lamp cord, similar to that described before, but see that between successive convolutions ½" cotton tape is placed in such a way that one turn of wire goes over the cotton tape, the next one under it, and so forth. There should be two such pieces of tape, one on each side of the “Cane Loop.” Then, when the loop is finished, the ends of the tape may be sewed to the insulation of the wire, and the broom handle may be slipped out. This gives a flexible sort of “snaky” loop which may be rolled up into a very small compass and placed on the inside of the portable set. When you need it, pull it out and let it hang down, to be used in this position. There are, of course, other ways by which to arrive at the same results, as, for instance, using thin twine instead of tape, etc. Another flexible loop of this kind can be made by winding the wire on a rubber hose, although this is not quite as effective, because it can not be rolled into such a small compass as by the other method described.

Notes

1. In 1914, both Edwin Armstrong and Lee de Forest applied “for patents on what became known as the regenerative or feedback circuit. One of the longest and most bitter fights in radio history resulted from this conflict over patent priority, leading in 1928 and again in 1934 to the United States Supreme Court.” While the courts decided in favor of De Forest, most historians give credit to Armstrong for the invention. Christopher H. Sterling, Stay Tuned: A History of American Broadcasting (Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002), 37. The super-regenerator was Armstrong’s improvement on the original design of his “Audion” tubes.

2. Gernsback is comparing the operative principle behind wireless telegraphy—Hertz’s discovery of electromagnetic waves—with its commercial applications. Referencing Marconi here is particularly apt, as “he was a highly competitive businessman whose ultimate goal was to establish a monopoly in wireless telegraphy. This goal was eventually referred to as the Imperial Wireless Scheme; Marconi meant to connect the entire British Empire together by wireless, and he meant to own the only company capable of doing so.” Susan J. Douglas, Inventing American Broadcasting, 1899–1922, Johns Hopkins Studies in the History of Technology (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987), 67.

Marconi’s “beam system,” or the Imperial Wireless Chain, first opened on April 24, 1922, and was completed June 16, 1928. “Imperial Wireless Chain,” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, February 2015.

3. The Type 199 vacuum tube debuted in December 1922 and was much smaller than any others that had come before it. It was “the first tube intended for use in portable receivers as well as in home receivers using dry batteries.” “UV199,” Radiomuseum, 2002, http://www.radiomuseum.org/tubes/tube_uv199.html.