Insurgent Geology: A Billion Black Anthropocenes Now

If, thus, we allow that an aesthetics is an art of conceiving, imagining, acting, the other of thought is the aesthetics implemented by me and by you to join the dynamics to which we are to contribute. This is the part fallen to me in an aesthetics of chaos.

—ÉDOUARD GLISSANT, Poetics of Relation

Counting her own theory, the theory of nothing, she had opened up the world. In every city in the Old World are Marie Ursule’s New World wanderers real and chimeric. . . . They wander as if they have no century, as if they can bound time . . . compasses whose directions tilt, skid off known maps. . . . They are bony with hope, muscular with grief possession.

—DIONNE BRAND, A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging

Black Geophysics and the “Unthought” Geoaesthetics of the Earth

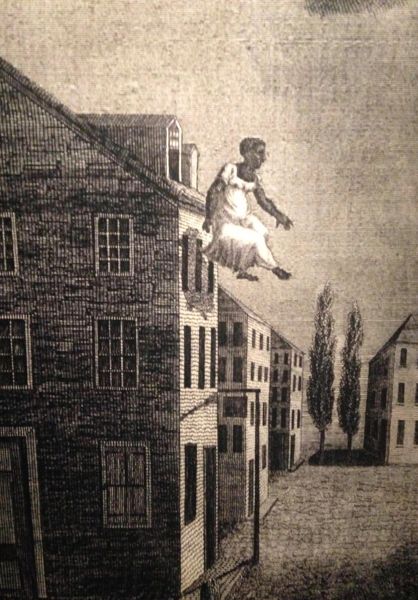

Inspired by the work of black feminist scholars—Dionne Brand’s poetry about “coming out a woman crushing stones,” Sylvia Wynter’s ideas from “Black Metamorphosis” on the “senses as theoreticians,” and Tina Campt’s “quiet aesthetics”—this chapter plots the course of a black geophysics crafted in the indices of fungibility and fugitivity, an aesthetics made in the provisional ground of slavery and its continuing afterlives (Hartman 1997). Focusing on three fugitive scenes—Steve McQueen’s paired films Carib’s Leap/Western Deep (2002), a print of a slave woman jumping from a window but suspended in a different gravitational field on display at the NMAAHC, and Brand’s character Marie Ursule in At the Full and Change of the Moon (1999)—I speak to the traffic between the categories of the inhuman in the White Geology of transatlantic slavery and in its Anthropocenic present. These images and Brand’s poetry of rocks insist upon what Campt calls futurity through the notion of “tense,” to offer an anterior possibility that cuts through coloniality as a counteraesthetic that refuses the inhuman in its codified state as property. Rather, the intimacies with the inhuman forged through “an aesthetics of chaos” are reworked in new poetic grammars to create an insurgent geology of belonging, one that refuses capture by geologic forces and redirects their nonstratified forces as a sense of possibility. These, what Campt calls “quiet acts,” might be thought as an “unthought” geophysics of White Geology, which gives another tense to the property and properties relation that emerged through the black hole of slavery, what might be called the black geophysics of “transplantation” (Wynter, n.d.) to a New World.

Wynter uses the term transplantation to reconceptualize how black bodies reclaimed a right to geography within the carceral confines of the plantation and their relocation across the Atlantic. She argues that black culture represented “an alternate way of thought, one in which the mind and the senses coexist, where the mind ‘feels’ and the senses become theoreticians. And black culture then and now remains the neo-popular, neo-native culture of the disrupted. It coexisted, and coexists, with the ‘rational’ plantation system, is in constant danger of destruction” (Wynter, n.d., 109). The idea of “senses as theoreticians” establishes how modes of experience are established in sense as a theoretical formulation of subjectivity made in the context of the denial of that subjectivity. This aesthetics or (political affect) is deeply political precisely because it relates to the possibility of life and its survival under conditions of violence. Citing how blues, and its unending part, without climax or end, established time outside of European sense of time and factory time, blues time is taken as space and a subversive territory of place; making of time into space creates territory free from enslaved labor, a counterpoetics, “subterraneanly subversive of its surface reality” (Wynter, n.d., 218). That is, “black oral culture of the New World constituted a counter-aesthetic which was at the same time a counter-ethic” (Wynter, n.d., 141). This thinking through sense achieved “the most difficult of all revolutions—the transformation of psychic state of feeling” (Wynter, n.d., 245, emphasis original).

Black Aesthetics at the End of the World

In Steve McQueen’s film Caribs’ Leap/Western Deep (2002),[1] two films are paired that tell the story of an act of suicidal escape and collective resistance in Grenada and contemporary gold mining in South Africa. It is a twined story of fugitivity and fungibility, of indigenous genocide and black bodies defined through the property of labor. Caribs’ Leap’s scene is 1651 Grenada, where the last Indian Caribs chose to jump to their deaths rather than submit to the invading French. It is an event that is said to have occurred at a cliff in the town of Sauteurs, now known as Caribs’ Leap. We see the figures always in mid-flight, never jumping or landing but suspended in an endless, ever falling body, gently held by the atmosphere. These figures defy gravity, seemingly floating indefinitely in the sky, never surrendered to the ground, cut alongside an image of a bobbing boat called Caliban and the shifting sands on a beach. Western Deep was filmed in the TauTona Mine (or Western Deep No. 3 Shaft) in the gold fields of the Witwatersrand Basin near Johannesburg in South Africa. The Western Deep mines are owned by AngloGold Ashanti, part of the international mining conglomerate Anglo American, and the basin held about 50 percent of all the gold ever mined on earth. The mines in the Witwatersrand Basin are the deepest mines in the world at nearly 3.9 kilometers underground and represent the furthest human bodies go into the earth’s depths. The mine employs nearly fifty-six hundred miners, who travel for an hour down the shaft to the rock face, where temperatures can reach up to 140 degrees Fahrenheit. In the deepest parts of the mines, the pressure above the miners is ninety-five hundred tons per meter squared, or approximately 920 times normal atmospheric pressure. The conditions can have serious, life-threatening consequences for the miners.

McQueen’s camera follows the shaft down, down into the earth, through dust, in the confined space of the cage, in the sheer near-darkness with a sound that reverberates in the concrete shell of the empty cinema through the tissue to bone. It is the black void of dark out of which nothing seems to emerge; then there is punctuation by an intermittent flicking light that allows a momentary sighting on location in the abyss, only to take us back down into it again. A terrible incessant industrial noise wails, visceral to nerve of teeth, exacting its excruciating assault on the body. After the shaft comes to the surface, the miners, dressed in their blue shorts, perform exercises, exhaustedly stepping up and down on a bench as red buzzers blare above their heads. The heaviness of their bodies on the edge of collapse, unfocused eyes from the dark void, all communicate the living death of their labor and the gravity of two miles of rock on flesh. Structured around the themes of descent, over- and underground, the films speak to a geophysics of anti-Blackness: self-destruction as quotidian subjection and fugitive collective escape. Cutting together gold and Blackness, past and future, McQueen tethers the dual corporeal effects of geology as territorial and psychic dispossession, a process of anti-Blackness that spans the two historical moments from 1651 to 2002. McQueen’s figures of ascent and descent draw on his own bibliographical connections to the island and the flying African folklore that drew figures escaping the terror of slavery through a shift of geophysics. Steve McQueen’s films together give us the surrogates of geology; slavery exposes the subterranean space-time of geology as a psychic and physical space. Sensibility here is not just thinking about exemplars of freedom and slavery but a practice of theorizing of how certain conditions pull and ground subjective possibilities within those twin natalities, possibilities that are infused with the individuation of liberal subjectivity and the collective refusal of that offering in what Glissant calls the “consent not to be a single being.”

Refusing the path of self-destruction, either through persistence in the violent property relation or through suicide, “flying Africans” (Synder 2015) was a genre that presented a possibility of “Making a Way Out of No Way” (NMAAHC), an alternative fungibility to the absolute fungibility of black bodies as extraction frontier. This “other gravity” might be thought in Tiffany King’s (2016, 1023) analysis of black fungibility as a spatial analytic, where “Black fungibility also functions as a mode of critique and an alternative reading practice that reroutes lines of inquiry around humanist assumptions and aspirations that pull critique toward incorporation into categories like labor(er).” King counters the absolute claim of fungiblity on the black body and its properties, tilting the axis of engagement. She argues that by “theorizing Black bodies as forms of flux or space in process rather than as human producers, stewards and occupiers of space enables at least a momentary reflection upon other kinds of (often forgotten) relationships that Black bodies have to plants, objects, and non-human life forms” (1023). Opening the state of possibility to the transformative intrarelations with other forms of life and nonlife unsettles and redirects the confinements of humanist prescriptions of what and how life is constituted. As King suggests, “black fungibility can also operate as a site of deferral or escape from the current entrapments of the human” (1024). Reclaiming fungibility from the bounded inscriptions of black social death opens and realigns the property–properties relation to speak to time-space coordinates that are not already occupied by the authorizing center, Colonial Man.

In another scene of refusal, Brand’s character Marie Ursule, a slave on the island of Trinidad in 1824 in At the Full and Change of the Moon (1999), plots a mass suicide as a quiet and defiant act of revolt (based on an actual mass slave suicide in 1802). Marie Ursule gathers the poisons, the potent vines, learned from forging connections to this new earth and its ecologies, from listening to the few Caribs “left alive on the island after their own great and long devastation by the Europeans” (Brand 1999, 2). Faithful to its plants, “she ground the roots to their arresting sweetness, scraped the bark for its abrupt knowledge” (Brand 1999, 2). Marie Ursule alone remains after the mass suicide, awaiting her death by the master, in order to witness his witnessing of this brazen act of wreckage on the plantation economy. Not taking the poison she has prepared, so that she can show them how she had devastated them, she says to the planters, “This is but a drink of water to what I have already suffered” (Brand 1999, 24) as she is beaten, broken, hanged, and burned. After two years with her one foot ringed with ten pounds of iron and the loss of an ear for an earlier attempt at escape, the queen of rebels turns her terror back to its point of origination: the master. After the mass poisoning of the Regiment of San Peur (without fear) society, the end of one world begets another: that of the descendants of Marie Ursule, queen of the San Peur. The morning of the suicide, Marie Ursule sends away her child Bola, and the novel follows her Caribbean diaspora across the geographies of the diaspora itself, from plantation to maroonage, through the centuries to the streets of Toronto and Amsterdam. When the proclamation comes by Sir George Fitzgerald Hill, lieutenant-governor in 1833, to end slavery, Brand displaces this “grudgeful news” that has come too late and admits too much, suggesting that “its authority is surpassed by the authority of Marie Ursule’s act ten years ago when she woke up to the end of the world” (51).

Marie Ursule’s New World and its genealogy of fragmentation, its wandering and desire, are told through the children of Bola, whose lives in the great fluidity of diaspora parallel the fluidity of the air and matter and rocks. Marie Ursule is remembered in the gathered impulses left in bones, in lives that spill over in the new world coming, “gestures muscular with dispossession” (Brand 1999, 20). Whereas slavery enacted terror, in Hartman’s (2007, 40) terms, “terror was ‘captivity without the possibility of flight,’ inescapable violence, precarious life. There was no going back to a time or place before slavery, and going beyond it no doubt would entail nothing less momentous that yet another revolution.” Such a revolution is exacted in the refusal of Marie Ursule through her quotidian relations with plant and geologic life that form an otherwise, which refutes the inhuman constitution of the fungible relation through the fugitivity of dispossession. The impossible becomes possible through a shift in the exchanges of inhuman fungibility. Overwriting the capacity for nonbeing in the diaspora, Brand’s materiality of language establishes the presentness of Blackness and makes that presentness an obligation with which to counter its erasure. Her poetry speaks the fungibility of the black body as flooded with the world. The earth, the weather, the ocean, and the tides and its materiality have a life in the work and world. It is a materiality that cuts through coloniality as a counteraesthetic, a poetry of rocks that tells a different story of rocks.

Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

Brand’s writing finds, haunts, and nudges against another image of a woman leaping, sleep walking, escaping, held in the suspension between fungibility and fugitivity. A woman is suspended out the window in an 1817 print at the NMAAHC. The text reads that she jumped out of the window after the sale of her husband and that she survived the fall. The wind catches and balloons her dress, but she is not falling. She has a different field of gravity that is held by a barely perceptible planetary shift in the allegiances of matter: “The problem was gravity and the answer was gravity” (Brand 2014, 157). She both escaped out the window and is not yet returned to the exposure of her captivity through the forces that would return her to the earth. The image possesses something of what Campt (2017, 5) calls the quiet amplification of “rupture and refusal.” In the geophysics of this image of the suspended woman, gravity is both the problem and the solution, rendering her invulnerable, held in the possible, awaiting a different tense of being. A different future. In another era, in the 1983 American invasion of Grenada, another woman is forced into conflict with the weight of this historical gravity of colonialism:

She jump. Leap from me. Then I decide to count the endless names of stones. Rock leap, wall heart, rip eye, cease breadth, marl cut, blood leap, clay deep, coal dead, coal deep, never rot, never cease, sand high, bone dirt, dust hard, mud bird, mud fish, mud word, rock flower, coral water, coral heart, coral breath. . . .

She’s flying out to sea and in the emerald she sees the sea, its eyes translucent, its back solid going to some place so old there’s no memory of it. She’s leaping. She’s tasting her own tears and she is weightless and deadly. She feels nothing except the bubble of a laugh each time she breathes. Her body is cool, cool in the air. Her body has fallen away, it just a line, an electric current, the sign of lightning left after lightening, a faultless arc to the deep turquoise deep. She doesn’t need air. She’s in some other place already, less tortuous, less fleshy. (Brand 1996, 241–42, 246–47)

In these images of another gravity, the printmaker and poet have, in Campt’s (2017, 17) words, strived “for the tense of possibility that grammarians refer to as the future real conditional or that which will have had to happen.” A woman is waiting, suspended above the earth in a different gravity. In the grammar of black feminist futurity, it is

a performance of a future that hasn’t yet happened but must. It is an attachment to a belief in what should be true, which impels us to realize that aspiration. It is power to imagine beyond current fact and to envision that which is not, but must be. It’s a politics of prefiguration that involves living the future now—as imperative rather than subjunctive—as a striving for the future you want to see, right now, in the present. (Campt 2017, 17)

If the woman who is fleeing out of the window is given an escape route that matches her own claim to possession of her body by the printmaker, her survival is doubly given in a disruptive grammar of geology; she has unbound herself in the very same language of matter that would make a person into a thing, defying the weight of her flesh arranged in the matter of anti-Blackness.

Hartman urges an attentiveness to how Blackness is made captive. Any recourse to the release of that captivity in descriptive moments of transgression that are held up as agency should be treated with caution in the “tragic continuities between slavery and freedom.” Imagining and representing scenes of “freedom” within slavery, a kind of hopeful overcoming, negates the way in which freedom and its conceptual apparatus were built on that subjection, with slavery very much in mind. That is, humanity was never for the whole of humanity, and freedom was only for some and a systemic regulation (and literal reproduction) of slavery for others. There is no recuperation of the captive or the captured in terms of agency within these positions and their legacy in the afterlife of slavery, because there is never the possibility of consent Hartman argues. The Black Anthropocenes or None is thus already a priori null and void. Drawing attention to a billion Black Anthropocenes is not a vehicle of visibility to see the dark underbelly of modernity with greater clarity, because it is already erased and caught in the process of erasure. So “Blackness” and “Slave” could be added to the ledger of Lewis and Maslin’s diagram of New World exchange as the sub- or surtext of racial difference and extraction, but that would do nothing to ameliorate that this was not an exchange by any conception of the imagination, only an “X” that marks the absence of that possibility. Slavery and genocide are the urtext to discussions of species and geology, their empirical bedrock and epistemic anchor. Another way to say this is that escape from captivity is only possible within the indices of that grammar of captivity and its interstitial moments, never as idealized outside of it. The deformation of inhuman subjectivity is made from within that matter, and so is its refusal and aesthetics of resistance. That is, to paraphrase Campt (2017, 59), to reread refusal not necessarily as “an inextricable expression of agential intention” but as a muscular refashioning, “bony with hope.” The destabilization of the inhuman as a category of chattel into an atmospheric, environmental sense and geophysical “tense” (Campt 2017) repositions the “event” in a different idea of time, space, and matter, an affective environment made through altered categories of description or aesthetics of the inhuman.

The colonial inscription that overwrites the inhuman as property and properties and its parallel geologies of displacement are aptly articulated by Brand (1997) in Land, written in the rifts of this geologic reason. She says, “Written as wilderness, wood, nickel, water, coal, rock, prairie, erased as Athabasca, Algonquin, Salish, Inuit . . . hooded in Buxton fugitive, Preston Black Loyalist, railroaded to gold mountain, swimming to Komagata Maru. . . . Are we still moving? Each body submerged in its awful history. When will we arrive?” (77). The places of Athabasca, Algonquin, Salish, Inuit, become “wilderness,” nickel, coal, prairie, commodities to be extracted. The Buxton community of black Canadians in Ontario, descendants of freed and fugitive slaves who escaped via the Underground Railroad; the “gold mountain” on the continental divide of British Columbia and Alberta, where Chinese migrants mined for gold; the black Loyalists in Preston and their waves of relocation by the British; maroons from Jamaica deported to Nova Scotia, granted less land in surveys for sharecropping than whites; the Komagata Maru, which brought British subjects from Punjab, British India, to Canada, and who were refused entry by the racist Canadian exclusion laws; the waves and waves of nonarrival and the uncertainty that can never reassuringly assert “you are Here” to confirm your place in the universe: this “unbearable archaeology” (Brand 1997, 73) of the geologic codes of dispossession time-travel to arrive in the racist impulse of the white cop who stops three friends in a snowstorm on the way to Buxton. These material histories sediment and arrive in the now as a continued challenge to presence in the context of erasure. They arrive as a geophysics of sense.

In Listening to Images, Campt develops an idea of “tense” as an affectual force of politics, enacting a movement toward a different theoretical possibility through the destabilization of the mode of encounter, listening rather than seeing the quiet soundings, blurring the authority of the visual code. She reorganizes the aesthetic sense of engagement away from the dominant reading of images as visual to attenuate both attention and a mode of reading resistance through tense (of the poise and noise of black bodies). Campt’s (2017, 16) work on photography’s quiet registers of meaning identifies an undercurrent in which we might read “possibilities obliquely . . . the tiny, often miniscule chinks and crevices of what appears to be the inescapable web of capture” in the “terms and tenses of grammar,” undercurrents that travel through more surface-led summations. She argues that the future can be conceived in terms of acts and political movements, but “I believe we must not only look but also listen for it in other, less likely places . . . in some of the least celebrated, often most disposable archives” (16). That is, decentering Eurocentric logics is not just a theoretical exercise of decolonization but a realignment of sense through affective infrastructures, an affective mattering in the discourse of materiality and its worlds. Campt says,

Futurity is, for me, not a question of “hope”—though it is certainly inescapably intertwines with the idea of aspiration. To me it is crucial to think about futurity through a notion of “tense.” What is the “tense” of a black feminist future? It is a tense of anteriority, a tense relationship to an idea of possibility that is neither innocent nor naïve. Nor is it necessarily heroic or intentional. It is often humble and strategic, subtle and discriminating. It is devious and exacting. It’s not always loud and demanding. It is frequently quiet and opportunistic, dogged and disruptive. (17)

Campt’s understanding of new arrangements of sense that are counterintuitive to the directional flow of readings that take place within the intellectual framework of Western liberalism enacts an axiological redirection of sense into new theoretical possibilities (affectual possibilities within the tight spaces of the quotidian rather than on their outsides). Reiterating Wynter’s call to take the senses as theoreticians, this unsettles sense and settles it into new formations that have a political charge precisely because they have a subterranean force that travels underneath and through colonial technologies of space and time. The printmaker’s gentle craft is to not subject the woman out the women to the gravitational field, to give her, or rather let her claim, another geophysics of being that does not subject her to an “inevitable” geo-logics of her designated material and symbolic position (a position that she has already claimed for herself in her leap). White Geology offers a geophysics of anti-Blackness, but the black woman held in countergravity expands the dimensions of geologic force through a different tense of possibility and relation to the earth. Rather than being framed in the “vexed genealogy of freedom” that forged the liberal imagination through “entanglements of bondage and liberty” (Hartman 1997, 115), she is partaking of a different gravitational opening, in Césaire’s ([1972] 2000, 42) words, “made to the measure of the world.”

In the lexicon of geology that takes possession of people and places, delimiting the organization of existence, the refusal of such captivity makes a commons in the measure and pitch of the world, not the exclusive universality of the humanist subject. I think of all the forced stoniness[2] that I have read in this past year through the literatures of slavery and its afterlives, the brittle broken rocks and bones forced together in mines, in the cut of cane on the plantation, the stoniness of bodies held against the imagination of a black life as an empty sign of property that positioned them as a receptacle for white desire and violence (per Hartman), the endurance of a stony patience that doesn’t forget love. Rather, this rock poetry finds that love is in the oceanic of the earth. As Brand (1997, 46) imagines slaves on factory ships, whose crank of the neck and tip of the boat reveal for a moment the horizon, “they moving toward their own bone . . . ‘so thank god for the ocean and the sky all implicated, all unconcerned,’ they must have said, ‘or there’d be nothing to love.’” Lilting, in the shit of the hold and the tip of the waves, “stripped in their life, naked as seaweed, they would have sat and sunk but no, the sky was a doorway, a famine and a jacket.” A refusal to be delimited is found in the matter of the world and a home in its maroonage; “they wander as if they have no century, as if they can bound time . . . compasses whose directions tilt, skid off known maps” (46).

Refusal might be understood in terms of the friendship of the “No” that Maurice Blanchot ([1971] 1997, 111–12) locates in the resistance to torture or oppression (perhaps influenced by his own experience in front of a firing squad)—a refusal that affirms the break or the rupture from an unacceptable logic and reason:

What we refuse is not without value or importance. This is precisely why refusal is necessary. There is a kind of reason that we will no longer accept, there is an appearance of wisdom that horrifies us, there is an offer of agreement and compromise that we will not hear. A rupture has occurred. We have been to this frankness that does not tolerate complicity any longer. When we refuse, we refuse with a movement free from contempt and exaltation, one that is as far as possible anonymous, for the power of refusal is accomplished neither by us nor in our name, but from a very poor beginning that belongs first of all to those who cannot speak . . . refusal is never easy, that we must learn how to refuse and to maintain intact this power of refusal, by the rigor of thinking and modesty of expression that each one of our affirmations must evidence from now on.

Tilting the axis of engagement within a geological optic and intimacy, the inhuman can be claimed as a different kind of resource than in its propertied colonial form—a gravitational force so extravagant, it defies gravity.

Forging a new language of geology must provide a lexicon with which to take apart the Anthropocene, a poetry to refashion a new epoch, a new geology that attends to the racialization of matter (see Silva 2017). Turning to critical black aesthetics is not an attempt to reformulate the Anthropocene into a different scene through black ontologies, ontologies without territories, but to locate more precisely how the praxis of that aesthetic, forged as it was within the context of inhuman intimacies that are inherently antiblack (constituted by the material geographies of colonialism, slavery, and diaspora), locates an insurgent geology. The origins of the Anthropocene continue to erasure and dissimulate violent histories of encounter, dispossession, and death in the geographical imagination. This geologic prehistory has everything to do with the Anthropocene as a condition of the present; it is the material history that constitutes the present in all its geotraumas and thus should be embraced, reworked, and reconstituted in terms of agency for the present, for the end of this world and the possibility of others, because the world is already turning to face the storm, writing its weather for the geology next time. We are all, after all, involved in geology, from the cosmic mineralogical constitution of our bodies to the practices and aesthetics that fuel our consumption and ongoing extraction. Our desire is constituted in the underground, shaped in the mine and the dark seams of forgotten formations that one day we will become, that we are already becoming. But our relation to the underground is different.

Inside the language of inhuman proximities, the ghosts of geology rise, naming storms, tornados, leaves, and rivers as experience. Césaire (quoted in Brand 2001, 58) writes,

I should discover once again the secret of great

Communication and great combustions . . .

I have words vast enough to

contain you and you, earth, tense drunken earth . . .