0. Practice immanent critique

1. Construct the conditions for a speculative pragmatism

2. Invent techniques of relation

3. Design enabling constraints

4. Enact thought

5. Give play to affective tendencies

6. Attend to the body

7. Invent platforms for relation

8. Embrace failure

9. Practice letting go

10. Disseminate seeds of process

11. Practice care and generosity impersonally, as event-based political virtues

12. If an organization ceases to be a conduit for singular events of collective becoming, let it die

13. Brace for chaos

14. Render formative forces

15. Creatively return to chaos

16. Play polyrhythms of relation

17. Explore new economies of relation

18. Give the gift of giving

19. Forget, again!

20. Proceed

“Good-Bye Condos, Hello Technological Arts”

The art and intellectual worlds in which we work, specifically in Montreal, are visibly conflicted, as much within the academic institution as among the many independent cultural producers contributing to the city’s international reputation as a creative haven. There is a general recognition that the conditions for research and creative activity have significantly changed with the rise of an increasingly speculative, high-turnover, innovation-driven “knowledge economy.” The “creative capital” fueling the economy tends to derive from fluid forms of social and intellectual cooperation often analyzed in terms of “immaterial labor,” defined as “the labor that produces the informational and cultural content of the commodity” (Lazzarato 1996, 133).1 These forms of value-producing collaborative activity tend, by nature, to overspill sectorial and disciplinary boundaries, and to fundamentally call into question the traditional split between “theory” or “pure research” on the one hand and “practice” or “applied research” on the other. Problematizations of that split, of course, are nothing new. What is new, in our context, is the extent to which policies intended to facilitate collaboration across the divides have been prioritized in government cultural and academic policies and in university structures. The way this has been done has created real opportunities—but also highly troubling alignments with the neoliberal economy.

In Canada, funding priorities have increasingly been angled toward team-based “interdisciplinary” research. Research projects are asked to justify themselves not only in terms of their academic value for their field but for their promised contributions to the advancement of Canadian society as a whole. Given the neoliberal global context, in which the category of “society” is increasingly subsumed under that of the “economy” (Foucault 2008), it has become more and more common to hear research results referred to in the economic vocabulary of “deliverables” produced for the benefit of “stakeholders.” Highly capitalized “centers of excellence” have been perched atop the university departmental structure, each advertised as “world class” with a mandate to address one or more issues of “strategic importance” to the wealth of the nation.

The arts have not been spared from the trend toward the neoliberalization of research.2 In 2003, a new funding category titled “research-creation” was introduced in Canada to encourage hybrid forms of activity promising to capture for research the creative energies of artists working within the academic institution.3 The turn toward the institutionalization of research-creation was framed in interdisciplinary academic terms: “to bridge the gap between the creative and interpretive disciplines and link the humanities more closely with the arts communities.” There was a clear emphasis on the role arts can and do play in the wider cultural field and a recognition of “the potentially transformative nature of research undertaken by artist-researchers.”4 At the same time, the program set in place a structure of standardized quality control and an accounting of quantitative results of the kind the arts have historically resisted.5 In the neoliberal context, the emphasis on making art-work accountable has the consequence, whether explicitly intended or not, of formatting artistic activity for more directly economic forms of delivery to stakeholders. The neoliberal idea is never far that artistic activity is most productive, and socially defensible, when it feeds into industry tie-ins helping fuel the “creative economy.” Moves within the academy toward institutionalizing research-creation are inevitably implicated in a larger context where the dominant tendencies are toward capitalizing creative activity. In that context, research-creation makes economic sense as a kind of laboratory not only for knowledge-based product development but for the prototyping of new forms of collaborative activity expanding and diversifying the pool of immaterial labor.

The same period in Montreal saw the inception of Hexagram, a multimillion-dollar “institute for research-creation in media arts and technology.”6 As originally instituted, Hexagram took the form of a private–public partnership with an explicit orientation toward tie-ins between university-based art practitioners and the culture industries as they were undergoing rapid digitization. This orientation was further emphasized in the 2005 move of Hexagram to a newly commissioned building dubbed the “Integrated Engineering, Computer Science and Visual Arts Complex” (“EV Building”). Developments like the foundation of Hexagram and the associated “integration” of the arts within an engineering “complex” served to further complicate the old split between “theory/pure research” and “practice/applied research” with a new divide between “traditional” art and “new media” art. During this period, projects involving digital media began to take funding priority over traditional forms. This is in no small part because they employ the same technological platforms as the increasingly computerized economy. Among other things, this construes Hexagram’s “art outputs” as products that are potentially patentable, saleable outside the art market narrowly defined. The faintest promise of patentability delivers creative activity to the category of “intellectual property” (IP). Where art becomes IP, the productively contentious issues—ethical, aesthetic, political, ontological—that have historically played themselves out around the place and nature of the “work of art” are backgrounded in favor of the economic annexation of the sphere of creative activity and the value-adding capture of its products.7

The economization of creative activity in Montreal is not confined to academic institutions. It begins to literally change the face of the city. In 2006, the city of Montreal embarked on a large-scale redevelopment of a central-city district into a new Quartier des Spectacles.8 The plan was dedicated to solidifying the city’s marketing position internationally as an arts-and-culture “Festival City.” The first visible step was a “lighting plan” to create a signage system to help rebrand the central-city area targeted for reinvigoration, which included the red-light district.9 The lighting project experiments with marking the urban landscape to make its repurposing visible, with the light motif attracting passersby to key sites. The red light of the district expands its connotation toward a vividness of experience open in a variety of forms to all who walk the streets, bringing to the fore local artists’ creative input on lighting and urban design. Here, research-creation extends to urban “experience design” with a mission to facilitate another industry tie-in: the tourism and hospitality industries. Experience design in light, annunciatory field-effect of a concrete remobilization of a coming arena of urban operation, has shown the way. The spotlight then turned to major construction and renovation projects as the Quartier des Spectacles’s urban redevelopment scheme entered its central phase. Art-research in practice has contributed to the opening of a major portfolio in the city’s economic strategy. Arts-related redevelopment strategies have even spread to the rural areas of Quebec. Headline about redevelopment plans for a southern Quebec ski station fallen on hard times because of climate change: “25-Million-Dollar Tourist Project: Good-Bye Condos, Hello Technological Arts.”10

At the heart of Montreal’s Quartier des Spectacles lies the Society for Art and Technology (SAT).11 The SAT grew from a successful organizing effort on the part of key personalities in the budding electronic music and digital arts community of Montreal toward hosting the international symposium of the Inter-Society for Electronic Arts (Montreal, 1995).12 From this seed, it has grown over the years into a central institution in the arts-and-culture mix of Montreal and become a magnet institution in the Quartier des Spectacles, all the while taking care to retain its community-based ethos and openness to experimentation. Its activities have expanded to include research programs into new design practices, the creation of digital platforms in partnership with independent producers as well as university-based researchers, technical training programs for cultural producers, cohosting of arts festivals, organization of public lecture series and colloquia, and projects to reconceive the form and function of the art gallery and to reconceptualize the documenting and archiving of interactive and ephemeral forms of creative expression.

In the early years, we chose to base our projects at the SAT. Its positioning at the heart of Montreal’s digital culture, coupled with its continued commitment to traditions of artistic experimentation and openness to community-based cultural activism, made it a resonating chamber for the tensions—and potentials—afoot in the complex, shifting context we have been describing. However reticent we were of the direction many developments in the larger neoliberal context were taking, we felt a strong affinity with the creative energy and conceptual questioning at the heart of ventures initiated by the SAT, and were adamant about working in connection with community-based initiatives and not solely from the safe haven of the university. We were not interested in simply taking a critical stance, as if as university-based researchers/artists we stood outside the situation and did not ourselves participate in the new economy and in our own way profit from it. We wanted to work in the thick of the tensions—creative, institutional, urban, economic—and build out from them.

We were looking to inhabit otherwise, to practice what we call, following Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, an “immanent” critique. An immanent critique engages with new processes more than new products, from a constructivist angle. It seeks to energize new modes of activity, already in germ, that seem to offer a potential to escape or overspill ready-made channelings into the dominant value system. The strategy of immanent critique is to inhabit one’s complicity and make it turn—in the sense in which butter “turns” to curd. Our project was to try to do our small part to curdle “research-creation’s” annexation to the neoliberal economy.

The category of “research-creation” was implemented in the larger Canadian institutional setting without a strong concept of how creative practice and theoretical research interpenetrate. At what level and in what modes of activity do they come together? In the absence of a rigorous rethinking of that question, the new category could do little more than become an institutional operator: a mechanism for existing practices to interface with the neoliberalization of art and academics. Key questions such as how the process of art alters what we might understand as research, or how art creates concepts, are backgrounded as institutionally driven issues take the fore, such as by what standards research-creation might be accredited. The drift is toward the professionalization of artistic activities, implying among other things the implementation of quantitative productivity measures.13 The danger, we felt, was that research-creation, once institutionalized in accordance with established criteria, would boil down to little more than grouping traditional disciplinary research methodologies under the same roof. This existing “interdisciplinary” tendency—where collaboration really means that disciplines continue to work in their own institutional corners much as before, meeting only at the level of research results—would do little to create new potential for a thinking-with and -across techniques of creative practice. Instead of asking how research has always been a modality of practice with its own creative edge, and how creative practice stages thought in innovative ways—how each already infuses the other—the instituted meeting between research and creation easily settles into a communication model revolving around the delivery of results among conventional research areas. For example, new sociological findings on the impact of technological systems, or on newly developed and as yet socially untested systems, might be made available to artists to see how they might creatively “apply” them (a potentially profitable exercise in such areas as gaming). We are of course not alone in exploring the reciprocity of research and creation toward a truly transdisciplinary exploration of new territories of practice.14 It is just that the counterexamples are numerous enough and prominent enough to produce a notable level of skepticism, if not outright cynicism, in certain quarters.15

It was precisely this sense that research-creation was troubled from birth that we took as our starting point. What if we started over? What if we took the hyphenation seriously, seeing it as an internal connection—a mutual interpenetration of processes rather than a communication of products? This approach would posit research-creation as a mode of activity all its own, occurring at the constitutive level of both art practice and theoretical research, at a point before research and creation diverge into the institutional structures that capture and contain their productivity and judge them by conventional criteria for added value. At that prebifurcation level, making would already be thinking-in-action, and conceptualization a practice in its own right. The two, we proposed, would intersect in technique, technique understood here as an engagement with the modalities of expression a practice invents for itself. Our speculative starting point was that this meeting in technique, to be truly creative, would have to be constitutively open ended. The kind of results aimed at would not be preprogrammed. They would be experimental, emergent effects of an ongoing process.

Experimental practice embodies technique toward catalyzing an event of emergence whose exact lineaments cannot be foreseen. As for Gilbert Simondon, the concept of technique as we use it includes the idea of the conditions through which a work or a practice comes to definite technical expression. Technique is therefore processual: it reinvents itself in the evolution of a practice. Its movement-toward definite expression must be allowed to play out. Technique is therefore immanent: it can only work itself out, following the momentum of its own unrolling process. This means that what is key is less what ends are pre-envisioned—or any kind of subjective intentional structure—than how the initial conditions for unfolding are set. The emphasis shifts from programmatic structure to catalytic event conditioning.

This idea of research-creation as embodying techniques of emergence takes it seriously that a creative art or design practice launches concepts in-the-making. These concepts-in-the making are mobile at the level of techniques they continue to invent. This movement is as speculative (future-event oriented) as it is pragmatic (technique-based practice).

What new forms of collaborative interaction does this research-creation-based speculative pragmatism imply? What kinds of initial conditions are necessary? What does it mean to organize for emergence? What are the implications of this emergent-event orientation for established forms of interaction, such as the conference, artist’s talk, or gallery exhibition?

The SenseLab was founded in 2004 by Erin Manning with the aim of exploring this problematic field. Dedicated as it was to a practice of the event, the SenseLab avoided defining itself in a formal organizational structure. It was conceived as a flexible meeting ground whose organizational form would arise as a function of its projects, and change as the projects evolved. Process would be emphasized over deliverable products. In fact, process itself would be the SenseLab’s product. Membership would be based on elective affinities. Anyone who considered himself or herself a member was one. The result is a shifting mix of students and professors, theorists and practitioners, from a wide range of disciplines and practices.

The first SenseLab event grew from a challenge arising from discussions with Isabelle Stengers,16 who expressed as a criterion for her participation in an academic event that it be just that: an event. In our conversations with Stengers, it became clear that for an “event” to be an event, it is necessary that a collective thinking process be enacted that can give rise to new thoughts through the interaction on site. It is equally important that potential for what might occur not be pre-reduced to the delivery of already-arrived-at conclusions. The SenseLab took as its challenge to adapt this criteria to research-creation. What makes a research-creation event?

Given the research-creation context in which we were working, it would prove crucial to avoid not only the communication model but also any paradigm of “application,” whether it be practical results from existing research and design disciplines as applied by artists to their work in their own field, or conceptual frameworks as applied to art or technology by philosophers or other theoreticians. Concept-work could not adopt an external posture of description or explanation. It would have to be activated collaboratively on site, entering the relational fray as one creative factor among others. The term “research-creation” was retained as a key term for an exploratory openness in this activity of producing new modes of thought and action. How to resituate the hyphen of research-creation to locate it as much within philosophical inquiry as artistic practice and between them both and other fields?17

The first event, Dancing the Virtual, took place in summer 2005 as the inaugural initiative in a series of events collectively titled Technologies of Lived Abstraction.18 This first event approached the problem from the angle of movement, specifically the question of what constitutes a “movement of thought.”19 The organizing refrain was a formula from philosopher José Gil, who was invited to participate in the event, that “what moves as a body returns as the movement of thought” (Gil 2002, 124). This concept holds that every movement of the body is doubled by a virtual movement-image expressing its abstract form, in its unfolding. The dimension of virtuality is at once the movement’s potential for thought and, associated with that, its potential for repetition and variation. Pragmatically, this concept built a self-referential dimension into the event. The event would gather into itself an awareness of its own abstract dimensions, accompanying its every move with a protoconceptualization in action: a thinking flush with its unfolding that would contribute to the self-piloting of what would happen.

The goal was in no way to reach agreement among participants on philosophical issues concerning movement, the virtual, and embodiment. The goal, rather, was to stage those issues, live, in the on-site interaction, to see if the interfusion of concept-work and embodied interaction would bring something new to participants’ practices, on the level of their own techniques or their techniques for joining their practice with those of others. Actual movement exercises were part of the activities.20 Philosophers were asked to put their thinking into movement, at the same time as dancers/choreographers were asked to move with their thinking (to mention just the two practices present that were most directly connected to the pivotal question of the event).

It was clear from the start that to succeed in getting philosophers out of their seats and put their thinking bodies into movement, and getting dancers untrained in philosophy to engage rigorously with difficult theoretical texts, without a crippling self-consciousness on either side, careful attention would have to be paid to the techniques used to design the event itself. The idea was that there are “techniques of relation”—devices for catalyzing and modulating interaction—and that these comprise a domain of practice in their own right. It would be the work of the event organizers to experiment with inventing techniques of relation for research-creation, not only as part of a practice of event-design, but as part of a larger “ethics of engagement.” The techniques would have to be structured, in the sense of being tailored to the singularity of this event, and improvised, taking the desires and expertise of the event’s particular participants into account, inviting their active collusion in determining how the event would transpire, so that in the end it would be as much their event as the organizing collective’s.

The success of Dancing the Virtual would be measured not by any easily presentable product produced during its three-day duration, but by whether there was follow-up on its process afterward: in other words, by whether the event itself had set anything in motion. The follow-up might take various forms: unforeseen cross-practice collaborations initiated at the event, other groupings elsewhere taking up the concept and practice of techniques of relation in the context of research-creation or other hybrid meeting grounds, and increased international networking between groups already working along similar lines. The focus in the creation of techniques of relation was on catalyzing a continuing collective culture dedicated to an ethics of engagement. We wanted to set into motion something that could grow and take us with it. In short, the event would be evaluated according to what it seeded rather than what it harvested.

This orientation made the event largely unfundable by granting agencies. The decision was made not to change the nature of the event in order to qualify it for government financing. This meant that if it was to come to pass, it would only be by the will and resourcefulness of its prospective participants, its community partners like the SAT, and its SenseLab organizing collective.21

Since the goal was to collaboratively “catalyze” movement toward the emergence of the new, the role of the techniques of relation would not be to “frame” the interaction in the traditional sense. The techniques would be for implanting opportunities for creative participation, which would be encouraged to take on their own shape, direction, and momentum in the course of the event. The role of the techniques of relation was to create conditions conducive to the event earning its name as an event. These techniques would have to be of two kinds: techniques to set in place propitious initial conditions, and techniques to modulate the event as it moved through its phases. The paradigm was one of conditioning, rather than framing. The difference is that conditioning consists in bringing co-causes into interaction, such that the participation yields something different from either acting alone. The reference is to complex emergent process, rather than programmed organization. Emergent process, dedicated to the singular occurrence of the new, agitates inventively in an open field. Programmed organization, on the other hand, functions predictably in a bounded frame and lends itself to reproduction.

A term was adopted for relational technique in its event-conditioning role: “enabling constraint.” An enabling constraint is positive in its dynamic effect, even though it may be limiting in its form/force narrowly considered. Take, for example, an improvised dance movement. The major constraint is the action of gravity on the body. As a cause, gravity is implacable, its effects entirely predictable. But add to gravity another order of cause, and in the interaction between the orders of determination something new and unforeseen may emerge. A horizontal movement cutting across the vertical plane of gravity can produce a certain quantum of lift temporarily counteracting gravity’s downward vector. The arc of the jump will be a collaboration between the action of gravity and the energy and angular momentum of the horizontal movement acting as co-causes. Add to the mix priming of the dancing bodies through techniques for entering into the movement and modulating it on the fly (including techniques of attention and concentration, as well as conceptual orientations) and a third order of co-causality actively enters in. Gravity has been converted from a limitative constraint to an enabling constraint playing a positive role in the generation of an event favorable to the improvisional emergence of a novel dance movement. This model of the enabling constraint was adopted for every aspect of the event-generating strategies for Dancing the Virtual and was retained for all subsequent events.

We wanted at all costs to avoid the voluntaristic connotations often carried by words like “improvisation,” “emergence,” and “invention.” There would be no question of just “letting things flow,” as if simply unconstraining interaction were sufficient to enable something “creative” to happen. In our experience, unconstrained interaction rarely yields worthwhile effects. Its results typically lack rigor, intensity, and interest for those not directly involved, and as a consequence are low on follow-on effects. Effects cannot occur in the absence of a cause. The question is what manner of causation is to be activated: simple or complex; functionally proscribed or catalyzing of variation; linear or relational (co-causal)?22

In the course of preparing Dancing the Virtual, we came to realize that we had embarked upon a highly technical process that could not function purely through free improvisation. This led to the emphasis on a certain notion of structured improvisation building on enabling constraints: “enabling” because in and of itself a constraint does not necessarily provoke techniques for process, and “constraint” because in and of itself openness does not create the conditions for collaborative exploration.

Setting up techniques of relation conditioned by enabling constraints facilitating co-generation of effects is a thorough and exacting process. It involved, in the case of Dancing the Virtual and all our subsequent events, a full year’s preparation.23 A technique, in all creative practices, from dance to art to writing and reading, involves practiced repetition and intensive exchange. In the context of an event that seeks to create a generative encounter between different modalities of practice, a technique involves activating a passage between creative forces.

Techniques as we understand them do not depend exclusively on the content of the practices but move across their respective processes at the site of their potential multiplication. A dance practice, for instance, will emerge across various registers. A movement exploration might co-combine with a conceptual force—a word, an idea, a landscape—influenced perhaps by past explorations and changed, probably, all along its course by improvisational explorations that connect to the experiment’s technical constraints. Similarly, a philosophical practice may emerge in and across a reading–writing register that cannot be restricted simply to content. Like the dance practice, the philosophical exploration is a technicity in its own right, activated and activating across registers of content and processual invention, moving incessantly between the rigor of denotation and the force of expression. Each of our events seeks collectively to find modalities of experimentation that connect practices at the levels of their intensive creative force. This is done not in order to map them onto one another, or to evaluate one in terms of another, but to propose a co-causal thirdness of exploration that can be generative of new modes of practice and inquiry.

Among the specific enabling constraints set in place for Dancing the Virtual were the following:

1. A ban was set in place as regards presenting already-completed work of whatever kind. This was not meant to imply that participants would enter as blank slates. On the contrary, they were encouraged to bring everything but completed work. They were encouraged to come with all their passions, skills, methods, and, most of all, their techniques, but without a predetermined idea of how these would enter into the Dancing the Virtual event. To encourage this, each participant was asked to bring something essential to his or her practice as an offering to the group: an object, a material, a keyword, a conceptual formula, a technical system. This relational technique was dubbed the “(Im)material Potluck.” The offerings would be kept on hand as a resource base for the event and would be called on improvisationally as needed and desired. Their immediate function would be as a gift to the group, as well as a kind of calling card expressing something about the person and his or her practice. This would facilitate entry into group interaction from the angle not of who someone was (their status in a field, their recognized achievements, the territory their achievements staked out for them) but rather of what moved them. What moved each participant became a potential co-cause of group movements in the making.

2. Everyone was required to read the same selection of philosophical texts in advance of the event. Certain periods of close reading and discussion of the texts would be included among the activities, both in small groups and in plenary session. This was not intended to force agreement on theoretical issues. The role of the readings was to give the entire group a shared set of conceptual resources that could be collectively mobilized, or used as pivots around which a recognition of different approaches would revolve. Whether collectively mobilizing or differentiating, what was important was that everyone be on the same page. To be avoided at all costs were general ideas and preassumed positionings. All conceptual commentary would have to create an effective link-in of some kind to the texts.

3. The ideas brought forth and the positionings effected would have to be performed in connection with texts everyone had read. This enabling constraint of “activating” ideas on site, in and for the group interactions, was essential given the differences in participants’ backgrounds, as well as differences in age and professional status. No common set of references could be assumed. To prevent one group or individual from being silenced or disqualified, each would be encouraged to “activate” what they knew or could do in a way that was anchored in a shared and always available print-based resource. This performative anchoring of each person’s contribution was especially important for bringing philosophy into the co-causal mix, given how potentially exclusionary philosophical language may feel to those in other fields. But the same principle applied to other areas as well: a simple movement exercise can be as intimidating to the perpetually deskbound theorist as an elaborate philosophical text is to the movement practitioner. This gave rise to an emergent technique of relation. Despite careful preparation, the philosophical plenaries at Dancing the Virtual and subsequent events did have a tendency to become just that: plenaries. In a quick regrouping after a Whitehead plenary that seemed to silence the nonphilosophers in the room, Andrew Murphie came up with a brilliant proposition: conceptual speed dating. This technique of relation has since become a mainstay not only at SenseLab events but in classrooms across the network. The proposition is this: take half the group and classify them as “posts.” Their job is to sit or stand or lie in position in a circular formation at the edges of the room. The other half are “flows.” As in speed dating, the flows move from one post to another, clockwise, at timed intervals. Next, find what Deleuze and Guattari call a “minor” concept—a concept that activates the philosophical web of a text without drawing attention to itself as a special term. This is where the real work comes in: the concept has to be understated enough that it has not yet entered common understanding and undergone the generalization that comes with that, but it must be active enough that the whole conceptual field of the work feeds through it. For Dancing the Virtual, the minor concept chosen was “terminus,” found in William James’s work (specifically Essays in Radical Empiricism). “Terminus” is a term that is often overlooked but is integral to the weave of James’s philosophy. It refers to the tendency orienting the unfolding of an event as it senses its potential completion and follows itself to its culmination. The terminus is a forward-driving force that carries an event toward its accomplishment. It is an organizing force exerted by the end, from the very beginning, and through every step.24 For the conceptual speed dating, the group is given the term, as well as a passage or page number to start from. At five-minute intervals, the flows move from one post to another, trying to sort out the concept. The force of the exercise plays itself out not only in the working-through of the concept in pairs, but perhaps even more so in the moving-forward to the next pairing, where a discussion takes up again, already infused with the previous conversations. This stages a collective thinking process, as individuals’ ideas disseminate and mutate through continually displaced pairings. In Dancing the Virtual, the conceptual speed dating had a catalytic effect, giving the event a pivot concept around which to unfold.

The constraint of “activation” was generalized as a rule against description or reportage, in keeping with the principle that a generative encounter could not be grounded prioritarily in content. We were concerned to create techniques that were capable of intensifying the passage between different modalities of experimentation, and specifically between small- and large-group processes. The question was how to generate a process for passing-between that did not deintensify what came before. The commonly used technique of summary “reporting” to “explain” what happened in a small group to the larger group tends to do little more than break the movement between and dampen co-causal synergies. The performative was chosen in this context as well, as a transitional mechanism. What happened in a small-group session had to be activated in capsule form for the group as a whole. If language were used for this, it had to be language that was not simply descriptive or denotative, but conveyed a performative force. A concept-working group, for example, might decide to reperform a discussion of a philosophical problem in the form of a movement exercise. We were continually asking ourselves how to create modalities of transition that captured not the content of the last exercise (be it artistic or philosophical) but its affective intensity (its generative force). The challenge was to recreate tonalities of experience across modalities—to make felt the intensity of thought in practice.

The focus on liminal activities, on the active transitions between phases of the event, had to take into account the inaugural passage: the initial passing of the threshold into the event. A major determinant to the success or failure of the event would be what participants brought with them through the threshold to the event in terms of their expectations about the coming group interactions and their individual status and positioning within them. How the initial entry is organized, and especially the physical layout and affective tonality of the space into which participants enter, influences the postures that will be assumed. The manner of welcome and the initial impression created of the space of participation are essential working parts of the event machinery, not neutral accessories. Together they constitute an apparatus of postural priming that embeds certain presuppositions and anticipatory tendencies in the event’s unfolding. The challenge was to disable participants’ habitual presuppositions—those tendencies engrained in all of us by the conventional genres of interaction in the art and academic worlds. Key was to find a mode of entry that opened the field of participation to unforeseeable interactions without destabilizing participants, rendering them reticent or defensive.

The passing of the threshold into the event would have to signal that what was coming was different from the norm and that the usual rituals of self-presentation and self-positioning based on achieved reputations and disciplinary stature would not be encouraged. This would have to be done in an inviting and even comforting way. A kind of hospitable estrangement was necessary. For the welcome, the model of hospitality was consciously adopted, rather than the more usual one of gate keeping and accreditation (registration, identification by institutional affiliation). But what we wanted to stress was not our hospitability, our generosity, but the event’s own emergent modalities of hospitality. Participants were individually greeted and ushered past the threshold, where a space awaited that contained none of the expected accoutrements—no tables at the front for a presenter, no chairs in rows for an audience, no podium, no stage. Instead, a number of “affordances” presented themselves that did not take an immediately recognizable form, so that they had to be arrived at through exploration (for example, comfortable seating opportunities without actual seats). These were thought of as “attractors.” They were meant to encourage a certain active self-organizing on the participants’ part even as they arrived, based on an affective pull toward particular affordance rather than a prestructured setting into place.

This principle was also used to self-organize the first division of the participants into small work groups. Elements within the space were draped with colorful fabrics of alluring textures (primarily fake furs). To divide the group, participants were asked to move to the fabric attractor that most spoke to them. The resulting groups were thus formed on the basis of affinity, a common affective tending, rather than preinstituted categories (rank, discipline, content area of expertise). In Deleuze and Guattari’s vocabulary, this focused the unfolding of the event on “minor” tendential movements rather than “major” structural categories. The overall affective tonality participants were tuned toward in their induction into the event was playfulness—play being the minor tendency contained by every instituted structure, whose unleashing softens or disables postural default settings. A degree of play creates the potential for the emergence of the new, not in frontal assault against structure but at the edges and in its pores.

Participants of course still had their disciplinary stature, position in their fields, and postural habits. This was not denied. The point was not to create a fictional equalizing, as if we could simply step outside of structure. There is no denying that we all need structure of some kind for our professional and personal survival. We took to heart Deleuze and Guattari’s warnings about the dangers of too-sudden or brutal “deterritorialization” and the need for “sobriety” (which we understood in terms of the centrality of technique). The point was not to force a heroic struggle against structure, which too often leads into a “black hole” (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 161).25 The goal was altogether more modest: to prime people’s capacity for creative play in a way that directed them to the event’s own hospitality. This orientation in the event, we hoped, might give rise to reiterable movements of creative collaboration that would continue beyond this phase of the event process.

Attention flags. Bodies fatigue. Stomachs growl. It is remarkable the extent to which the conventional genres of artistic and academic encounter disregard these basic facts. It was important to us to attend to these constraints and build them into each event through a commitment to managing this most prosaic “biopolitical” dimension of the encounter, in as hospitable a manner as possible. Food was plentiful and presented in way that called forth the rituals of conviviality surrounding shared eating in noninstitutional settings. (Food as a technique of relation would become a motif for subsequent events.) Dancing the Virtual started a tradition that carried over into all our events: a napping affordance. A sleeping tent, with mattresses and pillows for a floor, was set up in a corner of the space as a place for jet-lagged participants to regenerate, or as a quiet refuge for those feeling overwhelmed or socially challenged by the event’s intensity. The sleeping tent created an internal threshold to the event’s outside. Participants could manage their own rhythm of withdrawal and reentry to the proceedings without entirely absenting themselves.

Dancing the Virtual was successful in the sense that it did create a momentum beyond itself, toward the next phase of experimentation. Collaborations began to take form that extended beyond Montreal. A second event bringing the energies back to Montreal was planned for 2007. Housing the Body, Dressing the Environment organized itself around a different, but closely related, question from that of the first event. The refrain for this event was a phrase borrowed from the architects/conceptual artists Arakawa and Madeline Gins: “What emanates from the body and what emanates from the architectural surround intermixes” (2002, 61). The area of exploration was the way in which the potentials expressed through embodied movement—and in their “return as the movement of thought”—exfoliate spaces of relation that settle into architectural form. Body and built surround were treated as phase-shifts of the same process: forms of life taking architectural form, their movements and potentials returning like an echo of the architectural surround to co-causal effect. For this event, generative feedback between movement on the one hand, and architecture and interactive spatial design on the other, played the role of the central organizing node that the interplay between corporeal and incorporeal or abstract movements had fulfilled for Dancing the Virtual.

The general approach and major orientations of Dancing the Virtual flowed over into Housing the Body. Many of the techniques of relation were reprised. The model of hospitality was fed forward in the form of an invitation to all the participants of Dancing the Virtual to return for Housing the Body. With the exception of two, everyone returned, which condensed our capacity to welcome new participants to ten, for a total of fifty.26 As with the earlier event, a reading list was sent to the participants for online discussion in advance of the date to provide a pivot for concept-work and its integrative alternation with embodied and hands-on work, toward a collective practice of structured improvisation.

The techniques of relation mobilized for Dancing the Virtual had organized themselves around liminal activities forming event-transitions. For Housing the Body, a mechanism was sought to bring the liminality of these techniques—their minor, affective, tendential tenor—more concertedly into the central activities. A new genre of technique of relation was envisioned for this purpose: “platforms for relation.”

A platform for relation is a setup, system, or set of procedures that is already tendentially operative, but rather than affording a specific function at first approach, is more suggestive of it. A platform for relation does work, it embodies a certain technicity, but it is designed in such a way that the limits and parameters of its potential functioning are not readily apparent. This strategic incompleteness makes platforms for relation function first and foremost as attractors offering openings for inventive interaction. Platforms for relation are not technical forms standing as end products of a design or creative process. They are germination beds for a process rebeginning. The platforms for relation were envisioned to jump-start existing collaborations and generate new projects, to gather the event’s unrolling around the incipience of technicities to come. The invention of platforms for relation was the enabling constraint for Housing the Body, Dressing the Environment.

The call for participation generated the first set of platforms, as each participant was invited to propose one. Then the core event-organizing group parsed the platforms into categories and reproposed them as collective platforms to the participants in a bid to limit the number of platforms to six. The platforms were then recomposed through affinity in the months previous to the event by subgroups working independently through the SenseLab’s online grouphub. On the public setting of a “writeboard,” the platforms were intricately planned, sometimes co-germinating across one another. All groups were encouraged to begin to collectively plan how their platform could become a three-day workshop for the event. Within a few months, participants had settled into their platforms and altered them to suit their needs and desires. What the participants did not know yet was that we would ask them to give their platform away after the first workshop, thus creating a contagion between processes. We fully expected some platforms to resist the violence of this decree and that some would fall apart for lack of participants. The idea was to create a process within a process that would allow unforeseen interventions and regroupings to unfold. For Housing the Body, the generative transitions would be between platforms as well as between small-group and large-group activity.

The “Sound Surround” platform was one that resisted regrouping and ended up twice as large (and twice as loud!). They proposed an invented instrument: a microphone embedded in ice.27 Various sounds of unusual quality could be made by percussing, caressing, or shaving the ice. The sounds of the melting ice dripping into a metal tray below were captured by another microphone. Both sound feeds were input into a computer, where they could be digitally mixed and altered. The challenge of the group proposing the platform was to explore the sonic potentials of this setup, what manner of sound instrument it might lend itself to becoming, and what it might offer as an instrument to the unfolding of the event. On the first day, percussion was the favored approach. The result was cacophony—and seriously percussed nerves all around.

By the third day, the approach had morphed. Microphones were set up throughout the space to add a continuous feed of ambient sound into the mix. The sound mix was then broadcast back into the room, forming a central-instrument / ambient sound feedback loop. The volume was kept to low levels. The result was to create a self-modulating ambient sound envelope that contributed greatly to the affective tonality of the event. The platform for relation had successfully given place to an inventive, relational emergence.

Throughout Housing the Body, Dressing the Environment, as was the case in Dancing the Virtual, we were (sometimes painfully) aware that all explorations at the edge of inquiry risk failure. Certain platforms for relation didn’t take off, or even collapsed, their attractive force failing to find the conditions for relational emergence in the given context. When that happened, either they dissipated entirely or elements of the platform combined with another. “Failure,” processually speaking, added a fissional and fusional dimension to the event that was not preplanned. From this point of view, failure was generative, a positive formative factor in the event’s self-organizing. A case in point was a regrouping that occurred on the last day of the “Around Architecture” platform that took a turn toward the outside of the event.28 The group improvised procedures to collectively explore the juncture between architecture and urbanism, in this case the SAT building and its surrounding neighborhood.

Failures, for the SenseLab, have come to be thought of as opportunities for the emergence of new techniques of experimentation: they push the collective toward an engagement with the limit of what can be thought/created in a particular context. Techniques of relation access their creative potential most when they operate at the edge of what they are preconceived to do. For this to happen, they must embrace the eventuality of their own failure as a creative factor in their process.

“Giving away” the platforms for relation was meant to set a relay in motion so that the potentials embodied in the initial enactment of the platform might drift and evolve into new and unforeseen collaborative activities. We hoped that the creation of new interplatform initiatives might result. Letting go was one of the event’s central enabling constraints. It would plan into the event the same kind of fissional-fusional evolution that failures facilitate on an unplanned basis. The injunction to let go was dropped on participants without warning. It came as something of a shock to the system and elicited a certain resistance.

The resistance itself proved productive because it required a collective working-out of the force of the injunction. In terms of its processual effect as well as in terms of the justifiability, relative to the event’s self-organizing, of imposing enabling constraints through a decisional act by a subset of those involved. This brought out issues related to the positivity of ostensibly “negative” constraints, and to the complex interplay of degrees of creative “freedom” and power of decision. It has always been a premise of the SenseLab that a purely consensual process deadens potential and that irruptions of decision are necessary for the vitality of a creative process. The innovation we meant to convey was the yoking of “decision” to “letting go,” practiced as an enabling constraint and a technique of relation, so that even in the case of an arbitrarily imposed decision, power would facilitate “power-to” and not “power-over.” Yoked to letting go, under the proper conditions of an ethics of engagement, arbitrary decision can operate as a condition of spontaneity that actually activates greater degrees of collective freedom.

This somewhat brutal intervention on behalf of letting go was undertaken to focus on the notion that to be a success in its own terms the kind of process the SenseLab was experimenting with would have to be essentially disseminatory. The projects were not about ownership, either of products or of the process itself. They were not about credit; they were about creativity. Ultimately, they were about processual contagion: how self-organizing techniques and intensities of collaborative experimentation can self-propagate. We hoped that participants would come to view their contributions as gifts to creative contagion.

The concepts of dissemination and the gift would return as central refrains in the next two events. Together, they evoke the potential for a different economy: a nonneoliberal alter-economy of creative relation responding to the larger contextual issues set forth in the first two events.

By the end of Housing the Body, Dressing the Environment, it was already clear that we needed to come up with a different model for collective grouping. Otherwise we were not going to be able to welcome any new people: the interactive format of the events had reached its practical limit in terms of the number of participants. There was also the problem of the episodic, exceptional nature of the events. This had initially been a strength. The first two events extracted participants from their embeddedness in the everyday of their local contexts, creating a vista for acting and thinking otherwise. Now, however, this strength of the events began to feel like a limitation in some ways, as participants returned to their home environments without necessarily being able to find ways of following up on the momentum they might have found through the event. Collaborations did spin off in a number of cases. But as long as the problem of how to propagate the techniques of research-creative relation that had been collectively invented through the events was not addressed, the collaborations were left exposed in contexts sometimes hostile to their carrying-forward.29 The limitative political-economic, intellectual, and institutional constraints that produced the need to seek engagement elsewhere in the first place threatened to clamp back down as soon as participants returned to their home turf. Added to that was the issue of travel costs to Montreal, both in terms of its stress on personal finances and on the environment. It was clearly time to experiment further. How could the collectively produced techniques for transformative ethics of engagement be disseminated outward, into participants’ respective home environments, in ways singularly self-adapted to each habitat? How could the process we were collectively creating also open itself to nonacademics or nonprofessionals who did not have access to travel funding? How could this dissemination be effectively spread to groups that had not been involved in prior SenseLab events?

Starting from discussions with Australian SenseLab members Andrew Murphie30 and Lone Bertelsen, the beginning of a new distributive mechanism was proposed that would seek to spark locally rooted collaborative intensities across the globe. The goal of our third event, Society of Molecules, was to find mechanisms and techniques that would allow us to mutually interact and influence one another, without the need for face-to-face encounter. The SenseLab would go remote. The problem was how to distribute self-organizing creative energies carrying potentially transformative force, while operatively interconnecting them at a distance: research-creation as action at a distance. Moving in that direction was a necessary part of one of the SenseLab’s larger goals: to contribute to a continuing collective culture dedicated to an ethics of engagement, operating on a larger scale and conveying a power of contagion.

In the year leading up to Society of Molecules,31 a number of enabling constraints were collectively brainstormed. Building on our planning conversations with the folks in Sydney, Australia, we knew that the global event would consist of correlated local events. Each local event would creatively address a “politico-aesthetic” issue felt by local participants to affect the quality of their lives. The “politico-” element referred to formative or organizational forces that were active in each local environment, but extended beyond it in a way that placed them in connection with other locales. Examples might be: forces of redevelopment or economic stimulus that palpably changed the culture of the city; forces propelling or responding to the movement of people across borders; environmental issues as they play out locally; issues of urban planning and the conviviality of public spaces; and the potential local derelict spaces offer for alternative cultural initiatives adapting strategies from other emplacements or linking into earlier political movements for local empowerment. Our proposition was that these larger forces be addressed from the specific angle of their local effect, but in cognizance of their wider significance and with an active attempt to bring their translocal dimension differently into play.

The “aesthetic” element referred to the need to respond creatively to these forces: positively and generatively. Finally, the local groupings, known as “molecules” (a reference to Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the “minor” as “molecular” versus “molar”) would comprise between three and ten individuals. Their politico-aesthetic interventions would last between three hours and seven days and take place during the first week of May 2009. It was also vital to us that the ban against “reporting” and the encouragement of affectively oriented performative mechanisms for making connective transitions would apply to relations between molecules.

No constraint of any kind was placed on the content of the interventions, in keeping with the earlier events’ problematization of the danger of content-based distinctions for a generative process. Neither was there any constraint on the form the interventions would take. Form and content would be entirely determined locally but remain open to the contagious influence of other local groupings.

The problem of performatively activating links rather than relying on reportage was exacerbated by the distributed nature of the event. Techniques of relation would have to be invented to connect molecules across cities and countries and even continents. Two approaches used in previous events were adapted to this purpose. The model of hospitality was hybridized to become one of diplomacy.32 This became the technique of the “emissary.”

Each molecule was invited to choose an emissary as well as to name a host. The emissary of each local grouping was paired with the host of another group. Sometime in the five months preceding the main event, the emissary would travel to the host group (virtual voyages were a possibility where resources did not allow physical travel). The time and mode of their arrival would be unannounced: the arrival of the guest had an element of the unexpected. The role of the emissary was to make “first contact” with the other local culture. To facilitate the meeting, “movement profiles” were compiled by the SenseLab and distributed to the emissaries. The movement profiles described the designated host’s habitual daily movements through the city so that if the emissary so desired, first contact could be made in a performative fashion, taking advantage of the element of surprise.33 Emissaries were encouraged to use physical address information and standard forms of communication like cell phones sparsely, focusing instead on “encountering” the host, guided by the profile. Upon meeting, the host’s job was to gather the local molecule together and treat the emissary to a “relational soup.”

The relational soup could be anything at all. The enabling constraint was that whatever form it took, it should give the emissary an experience of the host group—a taste of that group’s process, modalities of interaction and organizing, affective tonality, and concerns. Sharing an actual meal was a simple default option. Whatever the relational soup proved to be, the emissary would return home with a “recipe” for it. The recipe was something that packaged the relational-soup activity into a technique of relation that could serve as a formula to be adapted for use by the home group upon the emissary’s return if the technique of relation it encapsulated resonated with that group’s own process. The recipe was one of the ways letting go was integrated into the interaction, now tweaked toward a practice of the gift. The host group’s gift of a processual recipe was reciprocated in the form of a “process seed” brought by the emissary and left with the host group. The seed was sealed and was to be opened only after the event. It could be an object around which a group activity could be organized, or a set of procedures to be followed collectively. The simple default option of this technique of relation was an actual plant seed that would be cared for by the molecule in the period after the event.

The role of the recipe was to create conditions encouraging processual contagion in the lead-up to the event. The role of the seed was to leave a trace of that processual exchange that could be activated in the follow-up to the event. The idea was to surround the period of the main distributed event with a longer-duration continuity of relation based on an ethic of care.

The “care” involved was not a personal quality or a private subjective state. It was a collective practice of care: an enactive, technique-based concern on the part of each group for the process of another group and for the overall process in which all the groups were implicated. Care was considered an impersonal technique for an ethics of engagement taking a directly political (“diplomatic”) form. It was understood in terms of care for the event (like the event’s hospitality) in which a collectivity was equally but differentially implicated. Everyone was actively together in the event, in each case from a different angle of approach expressing the singularity of a local process networking with others. Collectively singular.

This notion of differential embeddedness in the unfolding of a collective, distributed event was explicitly a rejection of the notion of the “common.” Care organized itself not around the common but around the irreducibly singular. It concerned being-different-together and becoming-together as an expression of those differences, as part of a shared process participated in differentially. Care, as care for the event, assumes no commons, in the sense of an equality of access to a preexisting, valorizable resource. It assumes no commonality or ethos of consensus, in the sense of general characteristics or convictions adhered to by all. And it assumes no community, in the sense of a defining identity that precedes and determines a collectivity’s coming-together and sets a priori boundaries to that convergence. All it assumes is the eventful integration of group differentials, in and for the singularity of an event, for only as long as the event sustains its own self-organizing process.

In the end, seventeen molecules in fifteen cities around the world participated in Society of Molecules. Molecular interventions were of many types. As had been the case with the platforms for relation of Housing the Body, some of the interventions were specifically conceived for Society of Molecules, while other groups used already-initiated projects as focal points for integrating into the Society of Molecules networking process.

To give just a few examples of a molecular intervention, the San Diego–Tijuana molecule addressed immigration issues around the U.S.–Mexican border. They hijacked a public telephone booth on the Mexican side and converted it into a free phone by patching the connection into Skype. Mexicans who were deported from the United States or encountered difficulty entering were invited to use the phone to notify friends and family or to call for help.34 The Amsterdam group addressed issues of ecology and food practices. They foraged for edibles growing in the city and prepared a collective meal from what they found in the urban environment. One of the Montreal groups spent time observing the life of derelict spaces in the city slated for redevelopment: who used them, how they used them, what patterns of movement grew up around them, and how they were policed. They joined in the patterns of movement and tried to organize participatory encounters that gave a gift of conviviality to the ephemeral community they found. Among these was a “Lack of Information Booth” that invited the public to explore the missing links between the official view of the city and its redevelopment and the ground-level forms of life filling the pores in the urban fabric. The Ottawa–Gatineau molecule performatively, and ironically, addressed feminist issues. They celebrated the vagina dentata.

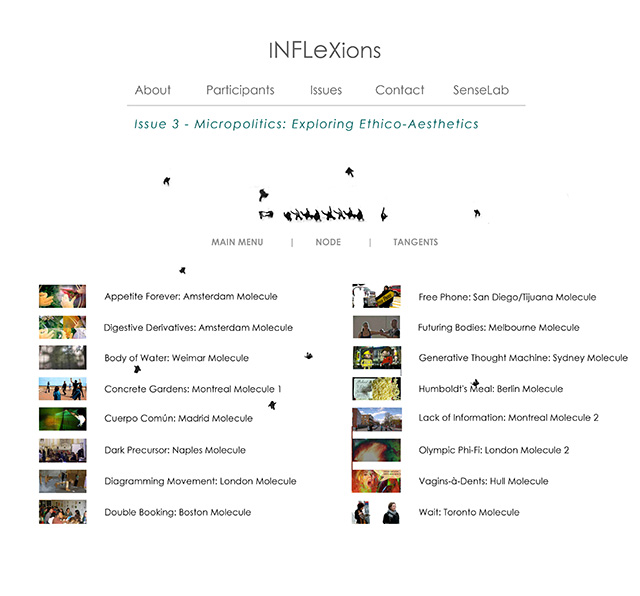

Inflexions: A Journal for Research Creation, issue 3. Designed by Leslie Plumb.

In the hope of building on the energies of the event, a special issue of the SenseLab journal Inflexions was prepared in the event’s aftermath that sought to continue the networking by further developing concepts activated through the event, and to showcase the inventiveness of the local actions.35

This third iteration of the Technologies of Lived Abstraction event series left a strong collective sense, at least at the SenseLab in Montreal, that it was indeed possible to invent techniques for generating aesthetico-political events across a distributive network with very little central input (beyond the setting in place of a skeletal framework of enabling constraints offering affordances for cross-fertilization). Recognizing the large number of collectives of similar inspiration working around the world under such rallying cries as “artivism,” “hacktivism,” “urban art intervention,” and “culture jamming,” there was a sense of participating, in one small way, in a larger process with unbounded potential for further networking and contagion. Society of Molecules also revived the dream of creating a “Process Seed Bank” that might provide the growing culture of this widely distributed ethics of engagement with a repository for sharing “recipes” for the diverse techniques of relation that have been put into practice across the world in different collective contexts. The SenseLab stakes no claim to originality with respect to these approaches and inventive practices. Its only claim is to participation in experimentation.

The final event in the series, like the first, relates to a challenge coming to the SenseLab from outside. Monique Savoie, founding director of the SAT, said she had been thinking about what an “exploded gallery” (galerie éclatée) might mean and how it might be invented. Her question came out of the SAT’s experience of constructing a gallery space for new media art on its ground floor. The gallery project had been unsatisfying, and was discontinued after a year. Savoie attributed the failure to the unsuitability of the traditional white-cube gallery model to new-media-based interactive arts, and to the traditions of ephemeral, performance-based art practices from earlier periods with which they are often in resonance. She envisioned a gallery that burst beyond the limits of the traditional model. What would a “gallery” be like that didn’t confine itself to formally delimited exhibition spaces but leaked out into the corridors and closets, through the administrative offices, onto the roof and across the building’s façade, saturating an entire architectural field? How could such a “gallery” extend its field even further, onto the sidewalk in front, to the mosque behind, through the inner-city park next door, toward Chinatown down the street, sending tendrils into the city surrounds? How could the reinvention of the SAT as an exploded gallery extend or intensify what research-creation can do, and how might that experimentation infiltrate, on its own exploding terms, the neoliberal project of the Quartier des Spectacles? Savoie gently suggested that helping answer these questions might be a project the SenseLab would be interested in taking on.

The seed for Generating the Impossible was planted. This final event of the series would take place in July 2011, during the rollout of a new phase of the SAT’s existence marked by the opening of a complete building renovation, including the addition of a third story topped by a large-scale interactive, immersive media environment in the shape of a dome (the “SATosphere”). The SAT planned to use the architectural rebuilding as an occasion for renewing its experimentation as an art institution, including a rethinking of the modalities of exhibition and kinds of creative events such an institution affords. (Please refer to the final chapter, “Postscript to Generating the Impossible,” for a brief account of how the event actually transpired. This chapter, under its original title, “Propositions for an Exploded Gallery: Generating the Impossible,” was originally written to share with other collectives as a contribution toward what we imagined might become a “process seed bank.” Once it began to take monstrous form [we had originally anticipated writing a short five-page piece!], we realized that extending our practice into a written document on techniques that have emerged over the past ten years would also allow us to take stock of where we had come to as a group and to collectively reorient toward the next event. Accordingly, it was written in the future tense. We have retained the original wording here.)

To ensure that this contribution also adds to the ongoing self-reinvention of the SenseLab, the approach the SenseLab has developed up to now will be turned on its head, in keeping with our exhortation to practice letting go. For each of our previous events, participants were asked to bring only their techniques and to leave their products behind, so that the meeting would occur at the level of the work’s technicity and its intensive capacity to propagate and vary. The space of encounter was always carefully conditioned and enabling constraints set in place. This time, on the contrary, we will ask people to come with all the products—papers, artworks, thoughts, ideas—that it pleases them to bring, as well as their techniques. As a further challenge, this cacophony will not be organized in advance: except renting a campground in the forest for all participants for five days (July 3–7, 2011) and directing our work toward the space of the SAT for the following three days (July 8–10, 2011), nothing will be done in advance to prepare the space of experimentation. One key enabling constraint will be the very injunction to begin the event under conditions of chaos, then move the event through a process of self-organization toward an “emergent attunement.”36

The challenge of “exploding” the gallery brings the SenseLab back to the specific context from which its explorations began: a questioning of the dominant genres of art-institutional practice; the problem of how dichotomies like those between pure research and applied research, and between creative practice and theoretical inquiry, can be challenged and then recomposed into a research-creation continuum.

Standard forms for the sharing of work—conference, artist’s talk, demo, exhibition, festival—operate according to generic templates. Each genre assumes a certain spatial disposition, time parameters, rhythms of transition, and modalities of interaction. The generic template is not unvarying, but sets recognizable limits to acceptable variation. Embedded in the genre is a certain understanding of how a work comes to experience. This includes what Jacques Rancière calls a “distribution of the sensible” (2005). Particular combinations of sense modes tend to be privileged above others, typically with one dominant sense foregrounded. The dominant sensory mode, combined with spatial, temporal, and transitional formattings, creates an economy of attention and emphasis that amounts to a value system. Implicit and explicit value judgments are thus primed into the event. Certain moments, and certain contributing factors, gain stature over others. The same is true of the people involved. The various distributive operations of the genre function primarily to assign differentially weighted roles to those involved (from the invisibility of building and technical staff to the overexposure of the star artist or academic to the backgrounded centrality of the audience’s watching—to limit the examples to the visual).

The enabling constraint of creative chaos is meant to disable these limitative constraints of generic formatting. The work of the event will be to confront the question of how a research-creation event can come to distribute the sensible differently, starting from the most minimal formatting. If one participant comes with a philosophical discourse to present and another with a cacophonous interactive sound installation, how can these two activities cohabit the same event? What kind of economies of exchange and reciprocity can make this possible? The activities brought to the event may well embody existing genres, but the space-time parameters into which they enter together will be unformatted, and the value weightings and distribution of roles indeterminate. Exploding a gallery will depend on how interference can be transformed into resonance. How does an event create an emergent attunement? Can a collective event–caring symbiosis emerge? If so, how can the public be brought into the process at a certain phase of the event’s unfolding in a role other than that of audience or spectator: as an active, co-causal factor in the event? Given the chaotic conditions, the task seems nothing if not impossible.

It is only out of chaos that the impossible can come. But as William James notes, there is no such thing as pure chaos. There is quasi-chaos: a field of divergences and convergences, comings-together and goings-apart, concatenation and separation, already tending to sort itself out in the determination of a thisness (James 1996, 65). Chaos, in and of itself, can never be experienced. What is experienced is the commotion of determinations-to-come vying for expression in an overfull field of potential relations. This quasi-chaos pulsates with potential technicities—as-yet-unstructured improvisations. This is why initial conditions of chaos can be an enabling constraint, and not just a disabling of existing genres. The vagueness of the event’s initial conditions enables it to come actively into itself, emergently modulating its dynamic form as it passes through the phases of its own occurrence. The event-in-the-making’s self-modulation in-forms an occurrent individuation. The event draws itself out into a line of formation that folds in and through its welling expression, describing the abstract shape of the event it will have been. From chaos emerges what Paul Klee calls the “pure and simple line” of an event of expression’s dynamic unfolding. Creative chaos is the self-drawing of a pure and simple abstract line, running from the commotional fullness of an impossible “what if” to the “here now” of an event risking its own singular individuation.

“Render visible,” Klee said; do “not render or reproduce the visible” (quoted in Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 342). What is rendered visible in painted forms, for Klee, are the generative forces in-forming the aesthetic event. For Generating the Impossible, we propose to activate the generative forces of a form of research-creation encounter—not so much render them visible as multimodally palpable, in an unforeseen unfolding composition of sense modes, spaces, roles, and rhythms of transition entering into unaccustomed resonance. Generating the Impossible’s proposition is to render palpable the force of the event’s self-articulating expression. This is a radical empirical proposition, in James’s sense of the term: the singular relational force of a welling event, as James emphasizes, is as real as any of the generic forms or finished contents that may enter into it as building blocks or come out of it as products.

An event’s relational force cannot be reproduced. It remains, always, a singular movement. It has a velocity, uniquely played out from the initial conditions at hand. It is potentializing, and renders potential. It follows the arc of a tendency working itself out.

Generating the Impossible proposes to intervene directly at the level of generative tendencies, in such a way as to render them palpably retrievable for new research-creation events. Tendencies are as singular as an event’s generative force, their “pure and simple line” resolutely connected to their eventful coming-to-expression in a specific time and place. They can be iteratively reactivated, to variable effect. We are not proposing to model what research-creation events can be. Instead, through the technicity of singular tendings, we are collectively, eventfully, setting into motion a metamodeling of emergence.

For Félix Guattari, to metamodel is to render palpable lines of formation, starting from no one model in particular, actively taking into account the plurality of models vying for fulfillment. Metamodeling takes forces of formation actively into account from the angle of their variations to come.37 The modeling is “meta-” because the lines it draws are “abstract.” They are abstract in the sense that the formative tendencies they map are eventfully more-than present, returning across iterations, in continuing variation. Events are both here-now, actual in their occasions, and always in excess of their present iterations. Metamodeling seeks to map their reformative excess.

A tendency, metamodeled, is an incipient assemblage (a platform for relation).38 The question of an assemblage emerging into occurrent attunement is, as always, a question of technique, as both Deleuze and Guattari and Whitehead emphasize. “The right chaos, and the right vagueness, are jointly required for any effective harmony” (Whitehead 1978, 112). For Generating the Impossible, the quasi-chaotic initial conditions for emergence include not only the specific contents brought by participants, and not only the plurality of generic forms in which they might be exhibited. They also include the accumulated techniques of relation experimentally assembled in past events. For Generating the Impossible, the presence of past participants will prepopulate the event’s emergence with collectively acquired tendencies vying for the opportunity to metamodel themselves in a new iteration under very different conditions than in earlier events.

The gesture of beginning this iteration from quasi-chaos with a minimum of conditioning extends the metamodeling of generative collaborative practices to fields of activity where the number and nature of the variables potentially entering into play are greater and even more unpredictable. It’s time to let them loose on the world at large.

The first phase of Generating the Impossible will take place in a forest camp north of Montreal. Participants will gather for five days of reading and hiking, playing and brainstorming, strategizing and swimming, provisioned if possible with a dynamic digital model of the renovated SAT building. In this low-tech forest environment, inventive means will be sought to activate new media work. There will be little time to read every paper, to think every thought people will have brought: this will be the quasi-chaos of our challenge. But we will come armed with concepts derived from a list of readings we will all read in the previous ten months.