One

About, Within, Around, Without

A Survey of Six Metagames

For one thousand and one nights, Scheherazade delayed her execution at the hands of the Shahryar by telling him a never-ending story. Adapted for European audiences by French archaeologist and orientalist Antoine Galland in 1704, textual compilations of Scheherazade’s tale of tales were translated from Arabic, edited to remove some of the more erotic elements (along with most of the poems), and supplemented with oral folklore that had no literary precedent such as “Aladdin, or the Wonderful Lamp” and “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.” Although there are many versions of One Thousand and One Nights, Scheherazade’s frame narrative is their common feature. Since the conclusion of Galland’s twelve-volume publication in 1717, One Thousand and One Nights not only continues to fuel an entire genre of orientalist fantasy but also serves as an archetypical example of metanarrative: stories about stories. From oral storytelling in West and South Asia to literary fairy tales in Europe to concert halls, ballet stages, theaters, and silver screens around the world, Scheherazade eventually found herself depicted within the collectible card game Magic: The Gathering (1993) (see Figure 1.1).

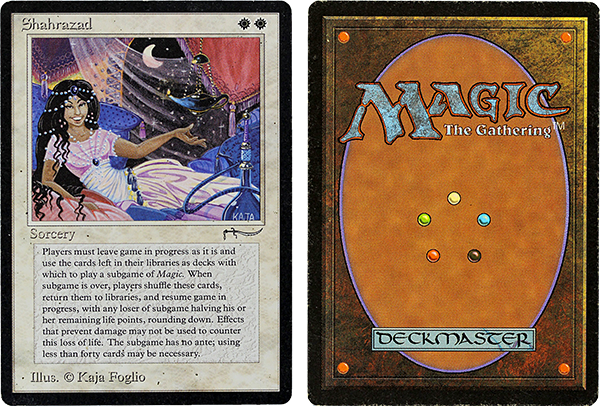

Figure 1.1. “Shahrazad,” a card designed by Richard Garfield and illustrated by Kaja Foglio, first appeared in the Arabian Nights expansion of Magic: The Gathering in December 1993.

After the initial release of Magic on August 5, 1993, the game’s creator and lead designer, Richard Garfield, worked on a strict deadline to finish its first expansion by Christmas that year (Garfield 2002). Authored entirely by Garfield and based explicitly on One Thousand and One Nights, the Arabian Nights expansion set included new cards based on myths and legends like “Flying Carpets,” “Mijae Djinns,” and “Ydwen Efreets.” Other cards in the collection reflected the cultural imaginary of post–Gulf War America, for example “Army of Allah,” “Bazaar of Baghdad,” and “Jihad.”[1] Finally, Arabian Nights portrayed classic characters from Galland’s One Thousand and One Nights such as Aladdin, Ali Baba, and, of course, Scheherazade. Illustrated by Kaja Foglio and printed for a limited time between December 1993 and January 1994, the game mechanics of the “Shahrazad”[2] Magic card match her myth. When the card is played,

players must leave game in progress as it is and use the cards left in their libraries as decks with which to play a subgame of Magic. When subgame is over, players shuffle these cards, return them to libraries, and resume game in progress, with any loser of subgame halving his or her remaining life points, rounding down. (Garfield 1993)

With “Shahrazad,” stories within stories become games within games. Thematically and mechanically, the figure of the storyteller stands in for Magic itself, a card game Garfield designed to both cultivate and capitalize on previously ancillary aspects of gaming not usually included within the rules like collecting, competition, and community. After all, the “Golden Rule” of Magic is that the rules printed on the cards take precedence over the rules printed in the manual—one thousand and one ways to play (Wizards of the Coast, 2014). One of the only cards banned in official tournaments (and one of the more valuable cards in Arabian Nights), “Shahrazad” is Richard Garfield’s (2002) favorite Magic card and represents the game within the game that he calls the “metagame.”

As discussed in the introduction, the term metagame has been deployed in Nigel Howard’s game theory, in Garfield’s game design, and by the players of roleplaying games like Dungeons & Dragons (1974) and collectible card games like Magic: The Gathering. However, over the past decade the term has been increasingly used within the networked communities who make, play, and think about videogames. Beyond Garfield’s (2000) examples of games “to,” “from,” “during,” and “between” games, the word metagame has become a common label for games about games, games within games, games around games, and games without games. The referentiality of pixelated indie games and Atari-based art installations is a mimetic metagame about videogames. The glitches exploited when speedrunning The Legend of Zelda (1986) or competing in Super Smash Bros. (1999) are material metagames within videogames. The psychologies of professional StarCraft (1998) players and their audience’s reactions during international tournaments are metagames around videogames. And the espionage and economy both in and outside EVE Online (2003) is a metagame of markets that operate without the videogame itself. If videogames conflate the magic circle of social ritual, the white cube of autonomous art, the black box of technical media, and the commodity form of capital into the ideological avatar of play, then these six examples of metagaming articulate a ludic practice that profanes the sacred, historicizes art, mediates technology, and de-reifies the fetish.

Difficult to design, impossible to predict, deeply collaborative, and always ephemeral, metagaming undermines the authority of videogames as authored objects, packaged products, intellectual property, and copyrighted code by transforming single-use software into materials for making many metagames. This chapter undertakes a survey of six specific metagames that emerge about, within, around, and without videogames. And although these six examples represent some of the popular practices and vocal communities making metagames today, they are by no means taxonomic or complete. Instead, the six case studies introduced in this chapter illustrate the broad range of overlapping practices that characterize twenty-first-century play. If the greatest trick the games industry ever pulled was convincing the world that videogames were games in the first place, then these metagames peek behind the curtain, unmask the magician, and spoil the illusion in the process of inventing new ways to play with loaded dice, fake coins, trick decks, and magic cards.

Indie Game: The Movie, the Industry, the Genre

Walking through Winnipeg in early 2010, Lisanne Pajot and James Swirsky stumbled across a striking image (see Figure 1.2). Buffeted by the winds above some strip mall parking lot or beyond the chain-link perimeter of a pea gravel playground, a piece of vintage videogame equipment swayed overhead. Instead of sneakers strung up by their shoelaces, a Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) controller dangled from a telephone line. How had it got there? Who had thrown it? And why would someone cast their controller up onto the wire? Whether celebrating the end of a school year or toasting the start of a marriage, whether marking the entrance to a crack house or memorializing the site of a street murder, the predominantly North American folk gesture of flinging footwear up onto unreachable public spaces sends a singular message: once crossed, certain thresholds cannot be uncrossed. When old shoes have seen too many steps, they are retired to an afterlife among the power lines. But in Winnipeg, someone had decided to play a different kind of game. Perhaps a bored player had hurled their old equipment up on a lark. Maybe the SNES controller was no longer seen as useful without the now-ubiquitous USB connection. Or it could be that the peripheral had simply been repurposed as raw material for a piece of street art. Whatever the reason, the intersection of mass telecomm with Nintendo equipment signifies the ways in which the aesthetic of retro videogames has been revivified within contemporary networks and networked culture. Swirsky made sure to return to film the abandoned SNES controller, not knowing that the found image would become the title card and iconic logo for his and Pajot’s documentary, Indie Game: The Movie (2012).

Figure 1.2. The image of a Super Nintendo controller tethered to a telephone line appears both at the beginning of Pajot and Swirsky’s Indie Game: The Movie and in the film’s logo.

Indie Game: The Movie follows the production of three independently developed videogames and the people who made them. Instead of featuring big-budget AAA software and the corporate culture of large studios, Pajot and Swirsky (2012a) focus on “the underdogs of the video game industry . . . who sacrifice money, health and sanity to realize their lifelong dreams.” Beyond the stories of Jonathan Blow and David Hellman’s Braid (2008), Edmund McMillen and Tommy Refenes’ Super Meat Boy (2010), and Phil Fish and Renault Bédard’s Fez (2012),[3] Indie Game: The Movie marks a historical moment in which the term indie game ceased to function solely as a label for a particular mode of independent production or digital distribution and became the common designator for a genre of videogames with a shared history and common aesthetic.[4]

Of the three games featured in the film, Pajot and Swirsky frame Braid as the successful forerunner. At the time of the filming, Braid had already shipped, garnered critical acclaim, and more than repaid Jonathan Blow’s personally financed, $200,000 wager. A relatively slow-paced, contemplative platformer that at least initially deemphasizes reflex action in lieu of puzzle solving, Braid’s pastoral, painterly landscapes are complicated by the player’s ability to pause, rewind, replay, and manipulate multilinear and multiscalar time. While a few games have incorporated the ability to reverse mistakes in real time,[5] Braid requires the player to game the game and use time manipulation not only to overcome precise platforming hurdles but also to navigate complex temporal puzzles and piece together the narrative of the main character, Tim. Through the Mario-like figure of Tim (an embodiment of the concept of Time), Braid weaves together three forms of obsessive, masculine desire: the ludic challenges of retro videogames, the courtly love quest for an unattainable princess, and the scientific models of technological progress that drive the military industrial complex.[6] The game explores the relationship between digital media and the atomic age, and between gamer culture and consumer behavior—a critique of in-game item collection, level grinding, and achievement hunting as well as the repetition of buying into the same videogame franchises year after year.

While Blow reflects on his success in the film Indie Game, Edmund McMillen and Tommy Refenes race to the release date of Super Meat Boy, a frenetic and fast-paced platformer driven by the twin logics of seemingly insurmountable difficulty and instant, infinite replay.[7] The eponymous Meat Boy, an anthropomorphic cube of meat with black button eyes and a toothy grin, leaves a trail of viscera as players maneuver him past saw blades and salt. Whether stopping on a dime or drifting along screen-wide parabolic jumps, Meat Boy’s rapid, repeatable actions stress the interplay among real-time control, spatial simulation, and “polish” that Steve Swink (2009, 8) calls “game feel.”[8] Like Braid, Super Meat Boy explicitly references (and shares an acronym with) Super Mario Bros. (1985)—an obvious metagame. In their game, McMillen and Refenes recast the classic love triangle between Mario, Princess Toadstool, and Bowser with their own Oedipal trio: the phallic hero, Meat Boy; the prophylactic damsel in distress, Bandage Girl; and the preemie homewrecker, Dr. Fetus.

Alongside Blow’s tranquil reflection and McMillen and Refenes’ impending release depicted in Indie Game, Phil Fish’s five-year legal, technical, and emotional struggle to make Fez provides as much dramatic conflict and anxiety as is possible for a documentary about computer programmers. Whereas Braid innovates in terms of time manipulation and Super Meat Boy profits from speed, difficulty, and repetition, Fez begins with a simulated computer crash that transforms Fish’s idyllic 2D pixelscapes through the mathematical logic of 3D rotation, translation, and projection (an anamorphic technique that appears in games like Echochrome [2008] and is further examined in chapter 2). Piloting Gomez, a small pixelated sprite wearing the titular fez, players wander through an eccentric world in which rotating the viewpoint does not simply shift the 3D perspective, but also reconstitutes the landscape according to the logic of the 2D screen.

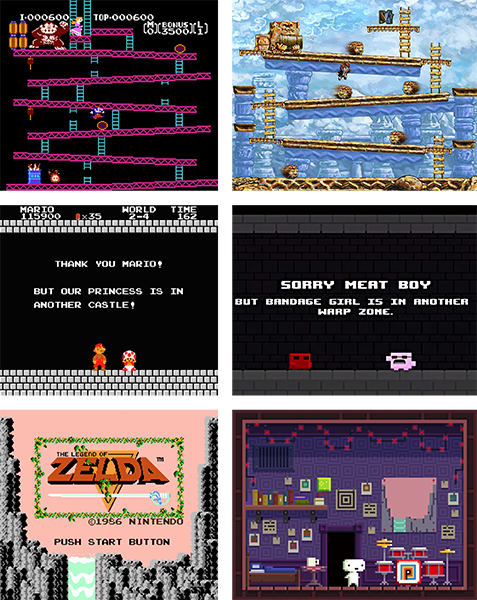

Despite the headaches and heartaches dramatized in Indie Game: The Movie, all three games were each wildly successful[9] and, although certainly not the first independently produced games, Braid, Super Meat Boy, and Fez represent the boom and subsequent gold rush in the late 2000s in which many independent game developers attempted to cash in on the emerging market for small-scale games that combine nostalgic graphics with novel mechanics distributed via online marketplaces like Microsoft’s Xbox Live Arcade, Sony’s PlayStation Store, Nintendo’s Wii Shop Channel, and Valve’s Steam. While the stories of Blow, McMillen, Refenes, and (eventually) Fish’s successes inspired other first-time game devs, Braid, Super Meat Boy, and Fez have something else in common in addition to the logistics of their independent production, digital distribution on Xbox Live Arcade, and massive sales: explicit references to the mechanics and aesthetics of the Nintendo Entertainment System in the mid- to late 1980s. Indie games, as an aesthetic genre, recover a history of play in the form of a metagame that represents, references, or otherwise cites the graphics and gameplay of other games. They are games about games (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3. Braid (top right), Super Meat Boy (middle right), and Fez (bottom right) explicitly reference videogames from the 1980s like Donkey Kong (top left), Super Mario Bros. (middle left), and The Legend of Zelda (bottom left) respectively.

As mentioned in the introduction, Andy Baio’s description of metagames as “playable games about videogames” is distinct from the more common use of the term to describe the history of play or the current popular strategies. In his blog post entitled “Metagames: Games about Games,” Baio assembles a long list of examples, noting that “most of these, like Desert Bus [c. 1995] or Quest for the Crown [2003], are one-joke games for a quick laugh. Others, like Cow Clicker [2010] and Upgrade Complete [2009], are playable critiques of game mechanics.”[10] Echoing Baio’s definition of metagame, in Indie Game: The Movie, Fish calls Fez “a game about games,” and the same logic could be applied to Braid and Super Meat Boy (Pajot and Swirsky 2012b). In Braid, Tim runs and jumps along faux Donkey Kong (1981) platforms, stomps Goomba-like enemies, and evades piranha plants from Super Mario Bros. (1985). At the end of each world, he encounters Mario’s signature flagpole flying an international maritime signal that attempts to warn the player against progressing further and a Yoshi-esque dinosaur who subverts the “I’m sorry, but the princess is in another castle” trope through an endless deferral.

Like Braid’s Mario-isms, McMillen and Refenes’ game is packed with Flash-animated parodies in which Meat Boy, Bandage Girl, and Dr. Fetus play out Oedipal versions of cutscenes from classic titles like Street Fighter (1987), Castlevania (1986), Adventures of Lolo (1989), Ninja Gaiden (1988), Mega Man 2 (1988), Pokémon (1996), Ghosts n’ Goblins (1985), Bubble Bobble (1986), and, of course, the original SMB, Super Mario Bros. On top of its many explicit shoutouts, Super Meat Boy’s various “warp zones” temporarily adopt the resolution and palette constraints of vintage platforms like Nintendo’s handheld GameBoy, feature Meat Boy–inspired art by other game designers, and, when completed, unlock characters from other independently developed games[11] like Michael O’Reilly’s hyperreferential I Wanna Be the Guy (2007), Anna Anthropy’s “masocore” platformer Mighty Jill Off (2008),[12] and even McMillen’s original animations for Tim in Braid (graphic assets that Blow ultimately decided to remake with Hellman). While these quotations appear to celebrate the cross-platform community of successful independent game developers, they also further establish indie games as a genre with similar graphics and gameplay, canonizing a cohort of other successful 2D platformers released in the late 2000s.

In the same way that Braid and Super Meat Boy remix retro mechanics and reference more than a few old games, Fez begins in Gomez’s bedroom, a pixelated square adorned with a low-resolution poster of the landscape from the original The Legend of Zelda (1986) title screen. After the player has climbed to the top of a tetromino town (made of various arrangements of Tetris [1989] blocks) and acquired the ability to rotate space, the world “crashes,” freezing the game on a glitchy kill screen before rebooting to a Polytron Corporation version of a motherboard’s BIOS readout. As the player goes about “defragmenting” the gameworld by shifting perspective to gather pieces of a monolith-like hypercube, another game emerges from within the game. The collectathon in Fez functions as a prelude to a cryptographic puzzle that initially required a massive, collaborative effort on the part of the players to first decode then deploy the hypercube’s instructions within the gameworld. More than just a coincidence, the fact that each of these indie games recalls and reinvents games like Super Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda, and Tetris reveals the personal history of these three designers and how play becomes a building block for a metagaming practices.

Over the course of thirty years, Super Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda, and Tetris have become platforms for making new games. If Jonathan Blow, Edmund McMillen, Tommy Refenes, and Phil Fish are any indication, these are the games with which Nintendo “zapped an American industry, captured your dollars, and enslaved your children” (Sheff 1993).[13] After the North American home console market was first saturated and then expunged in the early 1980s, Nintendo rebooted the medium by marketing their “entertainment system” as a children’s toy while designing the hardware to mimic those appliances already at home in the American den. As Jamin Warren observes in Indie Game, “for anyone that grew up basically after 1975, 1980 or so, we were the first generation to grow up with our parents giving us games . . . the first generation that grew up with videogames but not as an active purchasing choice” (Pajot and Swirsky 2012b). As indicated by the fact that no other women aside from Ed McMillen’s spouse, Danielle McMillen, is interviewed in the documentary, the unquestioned “us” in Warren’s statement is historical, geographic, and gendered. These indie games are not simply the byproduct of an independent or self-funded production or the result of the success of digital distribution platforms in 2008, but also reflect an aesthetic paradigm based on the history of North American men growing up in the eighties and nineties. From parking lots and playgrounds to early publications and consumer phone lines, the oral and transmedial history of playing console games lives on as a nostalgic memory, a design platform, and (according to the sales of these games) a successful marketing strategy.

While at the time of their release Braid, Super Meat Boy, and Fez distinguished themselves according to their unique graphics, inventive gameplay mechanics, and the personal histories of their developers, these differences are underwritten by a structural homogeneity based on their relation to the North American videogame industry in the late 2000s as well as a much longer history of cultural colonization and commodification of precarious labor. As Simon Parkin (2014) notes, “stories of sudden indie-game riches are appealing. They have a fairy-tale quality, the moral of which is often, ‘Work hard and you will prevail’ (even though this kind of overnight success is often the result of an un-replicable recipe involving privilege, education, talent, toil, and timing).” It is hardly a coincidence that Pajot and Swirsky’s three primary examples of indie games were each personally funded projects produced by two-person teams of young white men. It is also no coincidence that these examples were all 2D platformers with clever mechanics and retro references. And finally, it is no coincidence that they made millions on Microsoft’s digital distribution service. These coincidences coalesce in Indie Game: The Movie because the film itself mirrors the logic of the marketplace by deploying the term indie game as a way to valorize only certain kinds of precarious labor practices—the ones that paid off. The very concept of indie games circulates as a form of cultural imperialism that both colonizes profitable forms of independent production and sanitizes them for mass consumption. Adopting the term indie games from the much wider spectrum of creative and experimental labor, then applying it as a general descriptor for a specific form of game making, reduces all independent development to this particular aesthetic and mechanic genre of videogames and also reduces all independent developers to those white, North American men able to make a living developing games in the wake of the global economic collapse beginning in 2008.[14] Anna Anthropy’s (2012) blunt summary of the film is more direct: “White guys who grew up playing Super Mario sacrifice every part of their lives to the creation of personal but nonetheless traditional videogames.”

In terms of geographic space, Pajot and Swirsky’s admittedly compelling narrative ignores those modes of independent game development occurring in the gray-market releases of ROM hacks and language mods in China or the doujin fan games repurposing graphics from anime and videogames alike in Japan or the small, mobile games produced after hours with the borrowed resources of American and Japanese companies outsourcing to India (Shaw 2013, 184–85).[15] In terms of a longer timeline, independent game development did not begin with “indie games”—a point Bennett Foddy convincingly argues in his historical survey of independent game development during the 2014 “State of the Union” address at IndieCade East. As Foddy (2014) contends, the notion that Braid, Super Meat Boy, and Fez inaugurate the emergence of independent game development is a myth bolstered by the common historical narrative that the videogame crash of 1983 and subsequent commercialization of games for home consoles arrested independent production until the late 2000s. A longer history might start with the level editors shipped with Lode Runner (1983) and ZZT (1991) or the all-in-one game creation systems like Garry Kitchen’s GameMaker (1985) and the various Construction Kits of the 1980s. Mark Overmars’ re-release of GameMaker in 1999 and ASCII and Enterbrain’s RPG Maker in 2000 became viable platforms before the production of games within Macromedia’s Shockwave and then Flash took off throughout the 2000s. Ironically, the emergence of the term indie game as a label and genre in the late 2000s signals the moment independent game development became dependent.

Still swinging somewhere overhead, the purple and lavender buttons of a specifically North American Super Nintendo controller blend in with the cloudy Winnipeg sky. In Japan and Europe, the brightly colored, red, blue, yellow, and green buttons mimetically mirrored the Super Nintendo’s logo—a set of four circles, offset from one another in the signature colors of Nintendo’s mascot (the blue-and-red-clad Mario sporting a yellow cape and straddling a green dinosaur). By contrast, the buttons on the American, Canadian, and Mexican counterpart were replaced with more subdued hues. The logo itself, appearing on cartridge packaging and game manuals in North America, was converted from the RGB color scheme to grayscale hatching that aped the look of CRT interlacing. Although some criticized Pajot and Swirsky for their choice of interface, arguing that the red, black, and gray controller from Nintendo’s previous console, the NES, would have been a more appropriate icon for a movie about three eighties-inspired indie games, this distinctly regional controller is poetic in a different way. The sight of those purple buttons in the sky not only signifies the historical relocation of videogames from the home console to the networked clouds, but reveals a particularly North American form of ideology naturalized in the production of indie games. Whereas folk culture is often assumed to somehow exist outside of or historically predate capitalism, the acts of both shoe tossing and controller tossing signify the emergence of a postconsumer and aftermarket practice—a form of metagaming built not before or without, but after and within those discarded technical, historical, and cultural systems cast off the beaten “upgrade path” of global capitalism (Harpold 2007, 3).

A Giant Joystick: Alternative Control and the Standard Metagame

Before the Super Nintendo controller swayed in the breeze overhead, there was a giant joystick. Whereas controller tossing in Indie Game: The Movie signifies the metagame of a privileged group of designers that has since become a standardized aesthetic and software genre, there are countless other metagames that circulate outside the normative structures of play and production represented in Pajot and Swirsky’s film. What other interfaces swing alongside Nintendo’s classic controllers on telephone poles across America? The knobs, dials, and joysticks of the pre-D-pad era[16] of Odyssees, Fairchilds, and Ataris float alongside Sony’s and Microsoft’s now-ubiquitous USB devices (though many must also pile up on the ground, cordless). Mice and keyboards, balance boards and dance pads, Virtual Boys and Oculus Rifts, and scores of light guns also sway in the breeze. Beyond mass-produced interfaces, imagine all the mods, custom builds, and one-off oddities hanging on the wire. Imagine a quadriplegic controller with a series of sip-and-puff sensors mounted to a mouthpiece or a chin-controlled joystick assembled by hand and supported by a homemade PVC pipe and plywood stand.[17] Imagine an eye writer built by an international community to aid an L.A. graffiti artist with ALS.[18] Imagine wearable accessories for intimate, two-player performance art[19] or repurposed rumble packs for cybersexual encounters.[20] Imagine a giant joystick.

The controllers shipped with consoles, individually sold in stores and even remade within the aftermarket economies trailing the release of most mainstream videogame hardware, are designed to function as a standard interface between player and game. The Super Nintendo controller hanging in Winnipeg is just one part of a larger technological platform. In their study of the Atari VCS, Racing the Beam, Ian Bogost and Nick Montfort (2009, 2) define a platform as “a particular standard or specification before any particular implementation of it.” Within these standards, play is generalized in two interrelated dimensions. First, Super Nintendo games, for example, are explicitly designed in terms of a control idiom based on the states of twelve binary RAM values that map the states of twelve buttons.[21] In this sense, videogames standardize play by responding only to the changes within this set of discrete values. The umpire is automated within the mechanics of the software and every pitch is always already in or out, fair or foul, strike or ball—there is no in-between. Second, as a result of these binary buttons, players are standardized. Universal control assumes a universal body, and since the Super Nintendo controller was included as the default input for the platform, most games designed for the SNES anticipate bi-dexterous players (with two mobile hands able to act independently). Whereas standardized control standardizes play and produces normative players, alternative interfaces do not simply make videogames accessible, but radically transform what videogames are and what they can do.

From 9-volt AC adapters to North American controllers (and even the various chips within cartridges and consoles alike), the equipment packaged with and advertised as part of a videogame platform encourages players to conflate “official” hardware with the rules of the game—what could be called the standard metagame. As with “indie games,” the standard metagame operates as an unquestioned ideology structuring twenty-first-century play and comingling what happens in front of the television screen with a specific commodity. Despite the submarket of turbo controllers and Game Genies, in many cases using the “official” controller becomes an unspoken rule restricting play rather than one of many possible preferences. Games scholar and HobbyGameDev founder Chris DeLeon (2013, 7–8) boils this standard way to play down to five “meta rules”:

- Rule 1. The game is to be interacted with only by standard input controllers . . .

- Rule 2. The physical integrity of the hardware is not to be violated . . .

- Rule 3. The player should be directly and independently responsible for the actions made during the game . . .

- Rule 4. If playing against other players, the other players should not be disturbed outside the game . . . nor unfairly distracted within the game by meta commands that are not part of the core gameplay . . .

- Rule 5. The computer game should be played as released and/or patched by the developer.

Unlike the speed and scale of a videogame’s mechanical processes (e.g., the height of Mario’s jump or width of his hitbox), nothing is stopping the player from breaking DeLeon’s meta rules. Though it goes unsaid, this standard metagame structures the lusory attitude players unconsciously assume when picking up a controller and powering on a console. These meta rules are not a deterministic or involuntary mechanic but a completely voluntary result of a set of assumptions about videogames as a cultural commodity and mass medium. It is precisely through the popularization of the standard metagame that videogames begin to operate as the ideological avatar of play in the twenty-first century. Play as a synonym for possibility is replaced wholesale by the standard metagame. DeLeon (2013, 8) writes, “to return to [Bernard] Suits’ notion of rules as forcing inefficient play by making a golfer rely on the golf club to achieve the goal, the central rule of computer games is then that the player is supposed to rely only on the controller during play to achieve the goal state.” Change the controller, change the game.

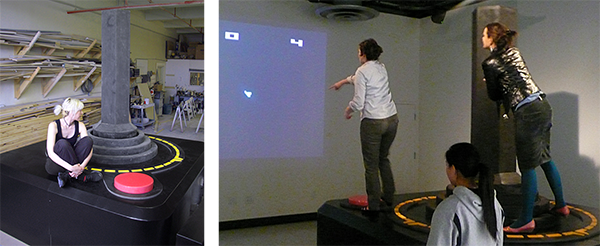

Two decades after the Atari VCS, or “Video Computer System,” defined a generation of 8-bit, cartridge-based home consoles, Mary Flanagan built [giantJoystick] (2006). According to Montfort and Bogost, Atari’s “rubber-coated black controller with its one red button [had] become emblematic of the Atari VCS and of retro gaming, if not of video games in general” well before Nintendo invented the D-pad (Montfort and Bogost 2009, 22). True to its name, Flanagan’s [giantJoystick] is a ten-foot-tall working version of Atari’s classic controller—a game about videogames in general (see Figure 1.4). Originally a commission for the Game/Play exhibit at the HTTP Gallery in London, [giantJoystick] looms large in the white cube, denaturalizing both Atari’s games and the site of play through a massive scale change. After climbing the three steps running alongside the left side of [giantJoystick]’s boxy base, players find themselves suddenly on a different kind of platform, wrestling the hexagonal, seven-foot-tall, anthropomorphic stick. The joystick is so large that no single player can easily manipulate both it and its accompanying red button. With Flanagan’s [giantJoystick] the privatized, domestic play of the home console era is made public and collaborative not through the networked connectivity of some massively multiplayer online game like Second Life (2003) or World of Warcraft (2004) but through a local, multiplayer metagame. Rather than leveraging official hardware, default controllers, or nostalgic representations of retro games to reinforce the standard metagame on contemporary platforms, Flanagan breaks the unspoken rules of that game through a scale change that activates play as a site for critical practice. The diminished, “childlike scale” not only invokes a culture of 8-bit nostalgia and child’s play, but deliberately attenuates the control and power of individual users (Flanagan 2006a). Instead of engaging in a fantasy of individual mastery or one-to-one input and output, communities of players adopt an arduous controller and challenge the ableist discourse structuring the ideology of the standard metagame.

Figure 1.4. Players collaboratively control Flanagan’s [giantJoystick] (left) at the opening of Game/Play at the HTTP Gallery in 2006 (right). Photographs by Mary Flanagan, 2006 (left), reproduced with permission; and Régine Debatty, 2007 (right), reproduced via Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 License.

Before building [giantJoystick] at DMC Fabrication in Brooklyn, Flanagan’s artistic practice explored play through academic research and social activism. A year prior to [giantJoystick]’s debut at the HTTP Gallery, Flanagan theorized a feminist game design philosophy through the concept of “playculture,” the title of her 2005 dissertation for the University of the Arts in London. In contrast to DeLeon’s five normative meta rules, in the catalog for Game/Play Flanagan (2006b) defines playculture as

first, the way in which participants engage in acts of subversion of many computer systems, and second, the way in which players perform and play with, in, and on such sites. Play is a social act, and computerised play makes actual technologies into “locations” for play. (Emphasis added)

Playculture articulates the time and space of what Flanagan (2009, 6) later calls “critical play.” Like playculture, metagames cannot be reduced to general, standardized modes of play. The metagame is not only the social, local, and performative site that Flanagan marks “with, in, and on” videogames, but also constantly (even if unconsciously, or only minimally) subverts the ideological assumptions that condition the culture of play. Although there is always a friction between the historically contingent acts of play and the abstract rules of institutionalized games, how can intervention occur within a standard platform when it is constructed, either physically or socially, in such a way that denies access to significant populations of people? How can change occur within a medium that many players never have access to in the first place? How can we become conscious of the fact that we are always playing, making, and breaking metagames (even when we do not know it)? Flanagan’s response to the lack of consciousness and inclusivity has been to change not only the controller, but the players.

In 1999 Flanagan founded TECHarts, “a community action project that encourages girls from the city of Buffalo and Erie County to receive an affordable hands-on education in computers, technology and media literacy” (Squeeky Wheel 2014). This was one of the early examples of the ways in which women are working together to reprogram the standard metagame. A decade later, groups like Dames Making Games in Toronto (est. 2012) and Code Liberation in New York City (est. 2013) regularly arrange meetups, workshops, classes, and spaces for women to learn how to code and make games.[22] These feminist organizations are designed as cultural platforms oriented less around the production of playable objects and more around community play, support, and solidarity. The result of such activities is a reinvestment in playculture as a practice that breaks all the rules of the standard metagame. Feminist game spaces (and the games they design) challenge not only the supposed individuality of play, the sanctity of hardware and software products, the authority of the original developer, and the generality of the standard controller, but also the lack of diversity that exists in contemporary game design, both independent and industrial.

Establishing the link between feminist theory and disability studies, Rosemarie Garland-Thomson (1997, 19) shows that “many parallels exist between the social meanings attributed to female bodies and those assigned to disabled bodies. Both the female and the disabled body are cast as deviant and inferior; both are excluded from full participation in public as well as economic life.” Along with the emergence of feminist cohorts, organizations like AbleGamers, AudioGames, and Switch Gaming have approached issues of access and embodiment from a different angle. As AbleGamers write in their manifesto on inclusive game design, “for the mainstream gaming markets, the best practices of universal design cannot be applied” (Barlet and Spohn 2012, 8). When it comes to bodies, there are no universals. The growth of relatively affordable[23] physical computing and 3D fabrication makes it possible for videogame controllers to be individually tailored through both DIY customizations and microeconomic models targeting specific bodies, not general audiences. Alongside custom fabrications like Flanagan’s [giantJoystick], individually or specifically modeled alternative controllers destabilize the distinctions between able and disabled bodies by demonstrating the radical specificity and irreducibility of both people and play that has always existed alongside the discursive abstraction of the normative player. The standard way to play is a matter of cultural and historical production—a not-so-lusory attitude toward videogames that privileges a normative, or standardized, body. Metagames like [giantJoystick] (as well as the blind and blindfolded playthroughs of The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time [1998], discussed in chapter 3) disrupt the dominant way we play, reveal the invisible rules guiding play, and offer an alternative to the standard metagame. Nonstandardized players use nonstandardized interfaces to play nonstandardized games. Disability is the rule, not the exception, and radical accessibility means individualized or specific—not standardized—control. There is no standard player and, in some form, every player is always already disabled.

Operating within Flanagan’s [giantJoystick] are the guts of another joystick: a Jakks Pacific plug-and-play, all-in-one controller-console. Not simply a USB device for Atari emulators like Stella or an aftermarket peripheral for the original 2600 platform itself, in 2002 the American toy company Jakks Pacific produced this stand-alone version of Atari’s iconic controller. Like Atari’s own Flashback series of plug-and-play consoles that can output to most televisions and projectors through a simple AV cable,[24] Jakks Pacific’s Atari-like joystick came with ten licensed games including arcade classics like Breakout (1978) and Asteroids (1979) alongside titles first released for home console like Yar’s Revenge (1981) or Adventure (1980).[25] Beyond solving practical problems related to the display and exhibition of retro videogames,[26] the joystick within [giantJoystick] conflates controller, cartridge, and console into a single object—literalizing the popular metonymy between interface and media. Matthew Kirschenbaum (2008, 36) calls this conflation a “medial ideology” that “substitutes popular representations of a medium, socially constructed and culturally activated to perform specific kinds of work, for a more comprehensive treatment of the material particulars of a given technology.” This is not “screen essentialism,” a term Kirschenbaum (2008, 31) borrows from Nick Montfort, in which graphics stand in for computing in general, but perhaps a kind of “controller essentialism” or an even more general “interface essentialism.” Interface essentialism means that all manner of interfaces, from standard controllers to a product’s packaging and even television commercials, not only represent but also reduce and replace their constitutive media platforms. Neither an official controller nor an Atari 2600, Flanagan’s [giantJoystick] compresses the platform to a single interface, and, in doing so, effaces the particularities of the Atari Video Computer System. [giantJoystick] is not a metagame about Atari’s popular controller or particular software, but a game within a game and about the games that occur around all videogames—an intervention at the site of play.

All the Categories are Arbitrary: Speedrunning The Legend of Zelda

as oot any% shifts back to vc-j, my mind wanders to the ess adapters

and to the virtual console, that doesn’t crash when gim is performed

and to the old kakariko route, resetting the console to save time

and to the timing method, the arbitrary start and end points

my mind wanders. (Wright 2015)

Before she quit speedrunning, before she got carpal tunnel syndrome, before she began hormone therapy, and before she wrote “all the categories are arbitrary,” Narcissa Wright made a living playing The Legend of Zelda. On her Twitch.tv channel in 2014, video capture of home console output was accompanied by webcam footage of glittery, viridian fingernails either grabbing a white GameCube controller or clasping a plug-and-play console—not a Jakks Pacific, but a handheld, Chinese version of the Nintendo 64 called iQue. Livestreaming on Twitch to an audience of thousands, Wright monetized her time spent speedrunning the original Japanese release of The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker (2002) and a rare Chinese version of its predecessor, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, released only on the iQue (see Figure 1.5).

Part an act of censorship intended to “protect the mental and physical development of the nation’s youth,” and part economic protectionism, at the turn of the millennium the Chinese Ministry of Culture enacted a ban “forbidding any company or individual to produce and sell electronic game equipment and accessories to China” (Clark 2013; Ashcraft 2010). With Nintendo, Sega, and Sony’s consoles relegated to gray-market goods, plug-and-play controllers reminiscent of the Jakks Pacific’s Atari joystick were manufactured to skirt the ban in mainland China. In 2003 Nintendo collaborated with the Chinese company iQue to build the Shén Yóu Ji or Divine Gaming Machine commonly known as the iQue player—a blocky, pseudo-off-brand controller-console that uses an external memory card instead of cartridges to load Chinese versions of Nintendo 64 games like Ocarina of Time and Super Smash Bros. Among many other subtle differences like a decreased number of polygons loaded at a time (which results in less lag), the display rate of Chinese text in the iQue release of Ocarina of Time is slightly faster than Japanese text and significantly faster than English. Whereas the Jakks Pacific installed inside Flanagan’s [giantJoystick] was probably selected as a matter of convenience despite its architectural differences from Atari’s original platform, Wright selected the iQue precisely because its various electrical and material discrepancies accelerated the Ocarina of Time metagame.[27] My mind wanders “to the ique player, the fast memory card, the old gamecube laser / to the ps2 disc speed, the sloppy port, the hd remaster / to the pal cartridge, the patched glitch, the japanese text speed / to the turbo controller, the rules / the rules!” (Wright 2015).

As the fifth installment of the classic series, Ocarina of Time represents Link and Zelda’s 3D debut, a daring reinvention of the action-adventure genre on the Nintendo 64 overseen by the original team members of Nintendo’s infamous R&D4: Shigeru Miyamoto, Takashi Tezuka, Toshihiko Nakago, and Koji Kondo.[28] Released when Wright was nine years old, Ocarina of Time defined that year’s Christmas and, along with Super Smash Bros., would occupy her time growing up in Steven’s Point, Wisconsin (Li 2014). After moving three hours south to study graphic design at Chicago’s Columbia College in 2007, Wright also became a student of the subculture of speedrunning. Quietly lurking on the forums at Speed Demos Archive (SDA), a community hub and clearinghouse dedicated to publishing and archiving high quality speedruns or real-time attacks, Wright learned that speedruns are “fast playthroughs of video games . . . [in which players] use every method at their disposal, including glitches, to minimize time” (Speed Demos Archive 2014). From one perspective, the goal of speedrunning is self-evident: play games fast. But conceptual clarity gives way to cultural, political, and practical problems. By adding an additional rule to the standard metagame, the speedrunning community not only changes the way games are played but also questions the very ontology of videogames. When does a game start and end? What is the definitive version of a given title? How do software and hardware technically operate? Why spend time playing the same game over and over? And—perhaps more immediately—who cares? Speedrunners self-consciously debate and collaboratively decide on answers to these questions which, when set in motion, function, like all metagames, as a form of game design. The voluntary rules invented by speedrunners, called “categories,” are metagames adopted by players that evolve in, on, around, and through the media ecology of hardware, software, and community comprising a game like Ocarina of Time. “All the categories are arbitrary / perhaps marksoupial said it best: / do whatever you want, there are literally no rules” (Wright 2015).

Figure 1.5. On Wright’s Twitch.tv channel in 2013 and 2014, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (right) is accompanied by timed splits (top left) and webcam footage of glittery fingernails (bottom left).

Completing a game as quickly as possible, a category that runners call “Any%” (in contrast to 100% completion), is the gold standard of speedrunning—a simple rule that can transform almost any videogame into a complex metagame.[29] How Any% is put into practice, however, changes according to that game’s community (as evidenced by the difference between real-time attacks and tool-assisted speedruns of Super Mario Bros., analyzed in chapter 4). Does the timer start when the console powers on or when the player first gains control after the main menu? Does the timer end when the last enemy is defeated, with the last input, or when credits begin to roll? What if there are no credits or final boss? What mechanics, aside from those outlined in the rulebook, can be exploited to save time? What gameplay sequences can be broken or skipped? Speedrunning categories are often more influenced by those aspects of a game that generate community interest and ludic pleasure rather than the orthodox ideologies or ontologies that define videogames in terms of authorial intent or technical operation. Instead of dogmatic adherence to hierarchical taxonomies and rigid definitions, there is a plasticity to speedrunning categories, which tend to multiply and transform as the metagame evolves through the community’s collective research, discovery, and exploitation of new techniques for playing each game. “All the categories are arbitrary” (Wright 2015).

Back in Chicago in the late 2000s, Wright (2013b) became obsessed with the programming infelicities in her favorite Zelda game, remembering, “It was my hobby in college to discover how memory manipulation works in Ocarina of Time, specifically Bottle Adventure Glitch” and, years later, a technique called ‘Wrong Warping.’” Most Nintendo 64 games (and many of the first generation of videogames with 3D graphics) can be mechanically exploited in terms of character movement, and Ocarina of Time has its fair share of collision detection failure, out-of-bounds exploration, and sequence breaking due to discrepancies between physics systems and animation states, especially at extreme velocities or angles of approach. The types of exploits that captured Wright’s interest, however, were those that directly exposed the computational logic of videogames by transforming the gamespace into a programming interface capable of both pointing to specific memory addresses and replacing their values at will. Hyrule is not just an interactive 3D environment but also an integrated development environment (IDE).[30] Whereas the Bottle Adventure Glitch allows players to arbitrarily write a predetermined set of hexadecimal values to the memory addresses that represent items stored in Link’s inventory (in order to produce unintended items), Wrong Warping allows players to write arbitrary hexadecimal values to memory addresses that correspond to cutscenes occurring within each geographic location in the game (in order to warp to unintended locations). Although manipulating memory is, in the broadest sense, what videogames do (like when Mario grabs a coin and the score is incremented or when he travels down a warp pipe and a new level address is loaded), exploits within Ocarina of Time let players update their inventory without grabbing the item or warp to a room without walking through the right door. Outside of authored sequences of combat, navigation, and dialog constructed according to the affordances of the various technical systems driving Ocarina of Time, unintended exploits like Bottle Adventure and Wrong Warp permit speedrunners to play the game within the game and invent metagames limited not merely by mechanical constraint but by the voluntary choices of players. “To warp or not to warp” becomes the question. My mind wanders “to the practice, the process, the savestate / to the gameshark, the game saver, the gecko code / to the cheating, the splicing, the policing / the audio waveform / my mind wanders” (Wright 2015).

Of course, there is no page for “Bottle Adventure” or “Wrong Warp” in the official manual shipped with Ocarina of Time. These exploits did not appear in strategy guides or even fan-made walkthroughs until well after Nintendo ceased production on the original cartridges.[31] Although official players’ guides work to both educate players on how best to enjoy Zelda and legitimize certain kinds of play, the mechanics of the game extend well beyond what is outlined on carefully constructed pages. Seemingly mundane or supposedly intuitive actions like creating a save file, starting a game, using the control stick to navigate, or squeezing the Z trigger to target enemies[32] are nevertheless just one, normative interpretation of Ocarina of Time’s complex functions. Beyond these “intended” mechanics, the incredible speed and enormous scale of digital media guarantees the emergence of exploits—recombinatory rules operating outside both the experience of any one player and even the expectations of the original programmers. For example, if a Nintendo 64 is powered on with the control stick tilted, that angle will be calibrated as the default position, altering the value of stick’s neutral position and, in the case of Nintendo 64 games such as Doom 64 (1997), permitting an extra range of directional motion—a position faster than fast.[33] My mind wanders “to the homebrewed wii, the region freed wad, / to the replacement joystick, to the hori mini pad, / to the rubber band, tape, and grease / my mind wanders” (Wright 2015).

In Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Videogames, Mia Consalvo (2009, 114) explains that “exploits don’t involve a player actively changing code in a game or deceiving other players; instead, they are ‘found’ actions or items that accelerate or improve a player’s skills, actions, or abilities in some way that the designer did not originally intend, yet in a manner that does not actively change code or involve deceiving others.” Adopting a similar attitude, Speed Runs Live (2014) allows all glitches because “the game merely executes the code in the way it was programmed to do. The game is the law. If you start trying to get at ‘developer intentions,’ then you start a game of guesswork trying to figure out what exactly was intended or not.” The ideology of speedrunning recognizes videogames exclusively in terms of a discrete state space produced by the operation of specific hardware and software (usually sanctioned releases by major companies, as is the case with Nintendo’s iQue). If videogames are agnostic to how they are played and every operation yields states of equal value, then there are no glitches, nothing is out of bounds, and the intentions of an author and audience are a completely arbitrary metagame in and of themselves. Furthermore, despite the fact that programmers and players alike may author algorithms to reliably arrive at a given possibility, there is both a formal and a phenomenal gap between the electrical manipulation of bits and bytes and the conscious experience of play. Although videogames operate in a cybernetic loop with and alongside human players through the contrivances of real-time control, they always execute outside individual experience. The possibilities of play are so immense that no one person could ever hope to access, let alone master, the range of games within these software sandboxes. Ocarina of Time is no different. Even after a decade of glitch hunting, there is always the possibility for new play to emerge through new discoveries, new attitudes, or new self-composed constraints. As Wright (2013c) admits,

While I believe pretty strongly that ‘you can always go faster, always,’ I do see people meeting goals and saying ‘I’m done! I’m done!’ The closest to that happening was when I got 4:57:XX for The Wind Waker before dry storage. Dry storage got discovered and I was reinvigorated to stay on top of the current metagame, and I have been ever since.

And she did. Wright went from forum lurker to prolific speedrunner, glitch hunter, community organizer, and, as of July 20, 2014, the world record holder for Ocarina of Time with an Any% time of 18:10 on the iQue. Of course, even after months trimming seconds and saving frames, Wright’s record was quickly surpassed.[34] My mind wanders to “the futility of it all. the statistical waiting game / grinding endless attempts, waiting for the outlier / never enough, suboptimal, improvable / my mind wanders” (Wright 2015).

Supported by forum posts, Internet Relay Chat (IRC) conversations, and the explosion of livestreaming in the late 2000s, speedrunning investigates the strange games already operating within videogames and expands single-player software into a massively multiplayer metagame. For the speedrunner, a live audience transforms private play into public performance, breaking up the monotony of repetitive practice through networked intimacies, gamifying the game through community feedback (and funding), and remediating everyday life into narrative. Even before Twitch.tv was launched in 2011, streaming services like Justin.tv, Ustream.tv, and even individually encoded Real Time Streaming Protocol (RTSP) feeds were being used to share speedruns. When Daniel “Jiano” Hart first pointed a webcam at his CRT screen, Wright knew streaming was the future of this metagame (Wright 2013d). In 2009, Wright teamed up with Hart to design the frontend of Speed Runs Live, a website based on a database and IRC bot Hart had programmed to register participants and record results of telematic races in real time. Suddenly, previously distinct, serial experiences of play became community events (initially called “impromptus”), through a simple network solution. Beyond publicizing “RaceBot”’s results, Speed Runs Live capitalized on Twitch’s popularity (and the service’s public API) to produce a stream aggregator in which any broadcaster previously registered with RaceBot is displayed on the website’s frontpage according to their current number of viewers. Speed Runs Live has since become a major community hub for speedrunning and, along with Speed Demos Archive, has begun to host and publicize community events like charity marathons. My mind wanders “to the rng, the frame perfect timing, the human error / to the attempts, the streams, the splits / to the audience, the shit talk, the cliques / the fame / my mind wanders” (Wright 2015).

In contrast to electronic sports or “e-sports,”[35] speedrunning has thus far remained comparatively uncommercial. The practice itself is not as easily molded to the template of broadcast sports and the community has been resistant to attempts to mainstream the practice.[36] This is not to say that the speedrunning community has not produced its own models of monetization. One of the most common ways that geographically isolated speedrunners gather is through the organization of large-scale online charity marathons like Awesome Games Done Quick (AGDQ) and its sister marathon Summer Games Done Quick (SGDQ). Since 2010, these biannual, week-long streaming sessions have become the public face of speedrunning. The practice of livestreamed telethons is becoming more popular as smaller groups borrow this fundraising model. The GDQs showcase the most accomplished runners engaging the most active metagames with donation readings and couch commentary by their peers. Organized by Mike Uyama and Andrew “romscout” Schroeder (with the help of dozens of volunteers) on GamesDoneQuick.com, since 2010 the GDQs have raised millions of dollars in donations for nonprofit organizations like Médecins Sans Frontières and the Prevent Cancer Foundation.[37] For Wright, as well as Uyama and Schroeder, what was once a full-time hobby became a full-time job. While speedrunning has not yet adopted sponsorship models and corporate funding like e-sports, a few speedrunners have started to make a modest living by coupling Twitch’s partner program with donation systems borrowed from the GDQs. With the success of both Speed Runs Live and her early Twitch partnership, in 2014 Wright quit freelancing and committed fully to a lifestyle sustained by subscriptions and donations of viewers.[38] My mind wanders “to the traveling, the marathons, / sexually harrassed, fleeing, hiding / reclusive, paranoid, getting high / playing smash, destroying my wrists / my mind wanders” (Wright 2015).

Wright’s annual performances at the GDQs were celebrated not only because of her skill, but because of her charisma and in-depth commentary. At AGDQ 2013 not only was she able to complete the Ocarina of Time in 22 minutes 33 seconds in front of a live audience of both local and telematic viewers, but she also recounted the long history of the Bottle Adventure Glitch and the Wrong Warp. Then, at SGDQ 2013, Wright returned with her iQue to introduce a hundred thousand people to the Chinese version of Ocarina of Time and further historicize the community’s discoveries. Scurrying past a now Chinese-speaking Saria and skipping the sword for a simple Deku stick is just the start of Link’s contemporary Any% adventure. While deftly manipulating the iQue controller, Wright commentated a “Naviless Aquascape” from the Lost Woods before “Super Sliding” across Hyrule Field. Her first challenge? Collecting Cuccos in Kakariko Village to attain an item of great significance—not the Triforce, but a bottle. In the spring of 2008, the first generation of Ocarina of Time speedrunners would then dash to the Temple of Time in order to prematurely “Door of Time Skip” and find a fishing pole in the future. In 2013 Wright simply “Save Warped” to the start of the game then bought a shield and “Mido Skipped” to access the Great Deku Tree. Backflipping across the empty basement after defeating the game’s first boss, Link landed on the edge of the blue warp that would normally conclude the dungeon. Instead, with the help of a bottle, Wright queued an animation state nicknamed “Ocarina Items” mid-jump in order to retain control of Link and manipulate the camera during the cutscene. Warping relies on specific frame counts, so Wright had to control exactly how many frames of the warp sequence were loaded. As Wright (2013e) explained, by exiting the “Ganondoor” on one of five precise frames during this sequence, the player can load one of five cutscenes including “child day,” “child night,” “adult day,” and “adult night” in Kokiri Forest and, serendipitously, a fifth memory address that points directly to the top of Ganon’s castle seven years in the future.

Suddenly standing at the top of Ganon’s tower, to complete this “link to the past” a child version of Link never meant to be played in the future must prepare for a seemingly impossible task: a “Hyper Extended Super Slide” off Ganon’s tower before fighting the final boss with nothing but a Deku stick. On the way, Wright (2013e) carefully avoided burning boulders because “Princess Zelda and a burning Deku shield cannot coexist”—a time paradox that also crashes the game when two objects from different timelines occupy the same memory address. From four hours to one hour to less than twenty minutes, for hundreds of players (and hundreds of thousands of viewers) Ocarina of Time has changed dramatically over the last decade as the Any% metagame evolved from the standard metagame to the Bottle Adventure to the Wrong Warp. At the beginning of her SGDQ run, Wright (2013e) mentioned that “a lot of people probably remember the AGDQ run earlier this year in January . . . and in that run I was talking about how after years and years we finally solved the category. Well, turns out this game never ends.” For speedrunners, the metagame never ends; you can always go faster . . . until you can’t.[39]

As Wright’s world record plunged from 18:56 to 18:41 to 18:40 to 18:32 to 18:29 to 18:10 throughout 2014, a game of virtuosic skill became a game of chance as play relied more and more on random events within Ocarina of Time. No longer a real-time attack but an attack on real time, the competition around popular speedruns are sometimes better measured in the weeks, months, and years that players spend rather than the minutes, seconds, and milliseconds each subsequent world record saves. As Wright puts it, “there’s, like, a 23 percent chance of something happening. If it does, you can continue the speedrun past the first eight minutes or so. So you have to play perfectly for eight minutes, and then only 20 percent of the time or so, you’ll actually get to continue” (Grayson 2016). After over 1,200 failed attempts to achieve 18:10, how long would it take to actually improve her world record? At some point, the human cost of speedrunning outweighs the desire to achieve a new record (leaving the record open for players willing to risk their time).

Shortly after getting carpal tunnel syndrome, deleting her Twitch account (temporarily), and beginning hormone therapy, Wright released a spoken word poetry on her new YouTube channel on December 17, 2015. Solemnly recited over a grainy, grayscale video of that critical moment before the “Hyper Extended Super Slide” on top of Gannondorf’s tower, Wright’s poem, “all the categories are arbitrary,” deftly weaves descriptions of videogame hardware, speedrunning techniques, community history, personal biography, and gender identity together into another kind of metagame that challenges the default categories of the normative ways we play. My mind wanders

to the life i poured into it all

working in a frenzy, managing a community

disrupting speedrunning

building upon it, something new and greater

and then it fell in upon itself

jiano saw it first; i was foolish

it couldn’t be unified; all the categories are arbitrary

finished painting my nails, doing my makeup

put on some mascara, roll up my thigh highs

all the categories are arbitrary

slip on a skirt, buy a new dress

feel the pain from the laser

all the categories are arbitrary

leaving the clinic, bottles in my hand

spironolactone, estradiol

all the categories are arbitrary (Wright 2015)

Kirby Kids and Master Hands: Super Smash Bros. as a Sandbox

Masahiro Sakurai first met Satoru Iwata at HAL Laboratory in 1989.[40] HAL was a subsidiary of Nintendo located in Chiyoda City, the metropolitan center of Tokyo, and Sakurai was only nineteen years old (Iwata and Sakurai 2008a). Whereas Iwata, a gifted programmer and project manager, would leverage his successes at HAL to become the CEO of Nintendo from 2002 through the Wii era until his much-mourned death in 2015, Sakurai was directly responsible for designing some of Nintendo’s most beloved yet idiosyncratic franchises: Kirby (1992–) and Super Smash Bros. (1999–). Kirby, a soft, pink, chibi-esque blob, is the eponymous hero of Sakurai’s first series and is perhaps best remembered for deconstructing the notion of “power-ups.” A design trope pioneered in games like Pac-Man (1980) and Donkey Kong (1981) and then expanded in Super Mario Bros. (1985), power-ups usually grant an avatar extra abilities for a limited time after picking up a power pellet, super hammer, or magic mushroom.[41] Building on the success of Kirby’s Dream Land (1992), a handheld platformer for the Game Boy, Kirby’s Adventure (1993) was released for the Nintendo Entertainment System one year later and further developed Kirby’s special skills. Not only could the kawaii character inhale air to float and suck up enemies for ammunition, but in Adventure Kirby could also swallow his foes to absorb a diverse array of abilities. Kirby’s Adventure featured twenty-six power-ups like “Cutter,” “Fireball,” “Hammer,” “Parasol,” “Spark,” “Stone,” “Tornado,” and “Wheel,” to name a few. Well beyond Super Mario’s suits or the weapon upgrades of Mega Man, the breadth of Kirby’s potential seems to undermine the whole point of the platforming genre. Why attempt to execute a series of precise jumps when Kirby can float at will? Why try to avoid enemies when Kirby can roll or slash or burst into flames to dispatch them? In this sense, Sakurai’s game design philosophy may seem too lenient in its attempt to appeal to inexperienced players but these critiques ignore Kirby’s greatest feature. The variety of game mechanics (many of which either avoid or bypass whole levels)[42] allow the player to not just choose how to play the game, but what game to play in the first place.[43] Kirby’s Adventure functions not only as a videogame with set rules in the form of mechanics, but also as a toybox that lets the player design their own metagames—a sandbox for building an assortment of castles. Beyond simply charting different paths through a given game, the metagame radically changes the game.

Almost twenty years after they first worked together, Iwata interviewed his ex-employee about the two-person prototype they had built together in 1998. Their “ultimate handcrafted project” would become Super Smash Bros., one of Nintendo’s bestselling franchises (Iwata and Sakurai 2008b). Charmed by Sakurai’s idea for a physics-based “four-player battle royale” on the Nintendo 64, Iwata urged the young designer to pursue the game full time while personally programming the prototype on weekends (Iwata and Sakurai 2008b). Kakuto-Geemu Ryuoh or Dragon King: The Fighting Game would only become Super Smash Bros. after its nondescript, polygonal characters and stand-in skybox—a photograph of HAL’s Ryuoh-cho neighborhood (which Iwata snapped from his office window)—were replaced with Nintendo’s IP. Super Smash Bros. is the first game to go beyond the Mushroom Kingdom and bring Nintendo’s famous first-party franchises together in one metaverse.[44] Although Smash Bros. is a game about games, unlike the indie game genre, Nintendo’s metagame does not simply cite the graphics and gameplay of their earlier titles but plays with intellectual property in order to cultivate their corporate brands.[45] Following the accessible design and mechanical variety of the Kirby series, and featuring the company’s mascots from Super Mario Bros. (1985), Donkey Kong (1981), The Legend of Zelda (1986), Metroid (1986), F-Zero (1990), Star Fox (1993), and Pokémon (1996), alongside characters from HAL franchises like Mother (1989) and Kirby, Sakurai’s Super Smash Bros. became a go-to, pick-up-and-play party game in the late nineties.

Despite the success of Sakurai’s self-professed approach to designing games that “first-time gamers could pick up without hesitation,” as always, something unexpected occurred (Iwata and Sakurai 2008c). With the release of Super Smash Bros. Melee for the Nintendo GameCube in 2001, players discovered that despite (or perhaps on account of) its open-ended design and dynamic mechanics, the game operated differently than most 2D fighters. Unencumbered by the sprite-based collision and metric motion and at the intersection of physics simulations and character animations, new mechanical exploits emerged as a game within the game. As with Ocarina of Time, there is no page for “wavedashing” in the Melee instruction manual, but air-dodging into the ground at an acute angle exploits the relation between the game’s physics system and character animations to introduce a quick, sliding motion—an exploit that “turn[ed] a popular party game into fierce competition overnight” (Beauchamp 2011).

In The Smash Brothers (2013), a nine-part documentary series that pulls together camcorder footage of basement tournaments alongside interviews of a diverse, grassroots community of competitive “Smashers,” Travis Beauchamp (Eastpoint Pictures 2013a) traces the decade-long history of play in this “sandbox fighting game.” As Chris “Wife” Fabizak (2013, 12–3), testifies in his deeply personal autobiography, Team Ben: A Year as a Professional Gamer (2013), in order to win:

First, learn to L-Cancel. By pressing the L button at the exact moment an aerial move hits the ground, lag following the attack is reduced. . . . Next, learn to short hop. Press and release the jump button extremely quickly and your character will jump half the normal height. . . . Now learn to dash dance. Hold the joystick to the side and your character will run . . . run back and forth within a specified distance and the turnaround is swift, giving your character flexibility in movement. Piece it together. The following maneuver should take less than 1 second: short hop, down air, fast fall, L-Cancel, shine, wavedash, short hop again. (Emphasis added)

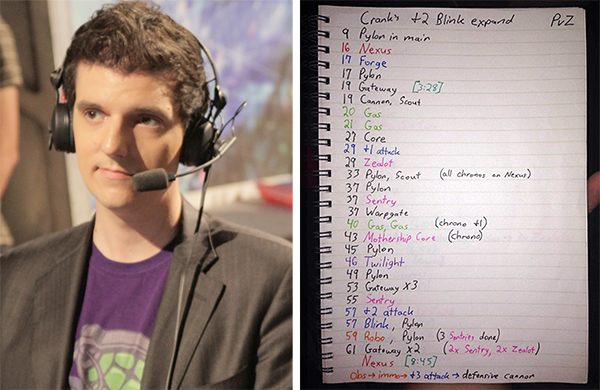

Driving along the eastern seaboard, from a gym in New Jersey to a rec center in Pennsylvania to a church in West Virginia to a mall in Ohio, Fabiszak began studying, taking notes, and learning about other players in order to master both Melee’s microtemporal mechanics and the community’s psychological mindgames before winning his first tournament based on “an unprecedented understanding of the Peach vs. Marth metagame” (Fabiszak 2013, 14). And he was not alone.[46] Across the U.S. and internationally, players began to explore the game within the game by chaining together mechanical exploits into combos, studying hitbox animations frame-by-frame, and analyzing the statistical data of both characters and players alike. Competitors, commentators, coaches, and even Narcissa Wright[47] banded together in city or state-wide “crews” to create a competitive game around the game despite Nintendo’s reluctance to embrace this community metagame.

Unlike Blizzard and Valve who, since the late 1990s, explicitly tuned their PC games to foster online and offline competition and in the late 2000s began to invest in e-sports as an advertising platform, Nintendo’s console games are designed to exist as islands, isolated from social networks due to lack of persistent player accounts, leader boards, and live chat.[48] Furthermore, and to the chagrin of the competitive Smash community, Sakurai’s Super Smash Bros. Brawl (2008) for the Wii actively discouraged the metagame developed in Melee by dramatically slowing movement, removing exploits like wavedashing, and adding a new, completely random chance to “trip” (and temporarily stun the player’s character) with every quick flick of the joystick—a luck-based mechanic that levels the playing field by lowering the skill ceiling. Chiding Sakurai’s design for the 2008 sequel to Melee targeting “first time gamers” on Nintendo’s family friendly Wii console, Lilian “milktea” Chen (East Point Pictures 2013b) laments the loss of Smash’s “duality of being able to be played as a party game and as a competitive game.” Whereas games like Kirby’s Adventure and Super Smash Bros. Melee allow for different styles of play, in the Wii era, Nintendo’s general design philosophy and lack of online infrastructure obfuscate their metagames. In the same way speedrunners continue to play Ocarina of Time, smashers continue to play Melee. Rather than “beating” their respective games and upgrading to newer versions, these communities make and remake the metagame that itself evolves over time within and alongside these software sandboxes.

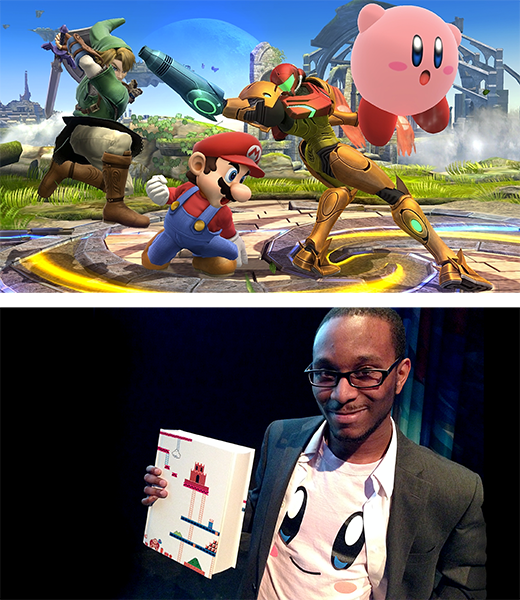

Figure 1.6. Sakurai’s signature character Kirby returns in Super Smash Bros. for Wii U (2014) (top), a figure that “metagame historian” Richard Terrell adopted for his moniker “KirbyKid” (bottom). Photograph by Patrick LeMieux, 2014 (bottom).

Beyond a chronicle of release schedules and review scores, metagaming indexes the material histories and community practices of play. On Critical-Gaming.com Richard Terrell (2011c) writes, “Every game with a metagame worth understanding deserves a devoted video game historian.” Similar to Beauchamp’s story of East Coast-West Coast rivalries and Fabiszak’s personal account of a “year as a professional gamer,” Richard Terrell’s (2011d) “Project M-etagame” is a record of the history of competitive Super Smash Bros. Adopting the moniker “KirbyKid,” Terrell was one of the few smashers to stick with Sakurai’s signature character in competitive Melee (see Figure 1.6).[49] Although Kirby is widely perceived as one of the weaker fighters within the Smash metagame, he is also a kind of meta-character able to steal the powers of every other fighter (not unlike the “Shahrazad” Magic card or Rubick, the Dota 2 hero who makes an appearance in chapter 5). Intrigued by the possibilities of Kirby’s improvisational play, Terrell adopted the character as his avatar to honor Sakurai as well as assume a self-imposed constraint—a metagame of his own making (Terrell 2010).

In “Project M-etagame” Terrell (2011a) offers a broad definition of metagaming as the “collective learned gameplay strategies/techniques” like wavedashing or short hopping; “behavioral trends” like quitting early or suiciding as a way to forfeit a competitive match; “modded controllers” like removing the springs in the bumper buttons on GameCube controllers for quicker L-canceling; “using cheats/glitches/exploits/guides” like unplugging a router to gain an advantage in networked games; and “any larger, connecting, overarching fiction” like the metaverse of Smash itself and the fan fiction it inspires. Whereas Flanagan’s modded Atari joystick breaks one of the rules of the standard metagame and Wright’s Ocarina of Time speedrun on the iQue adds an additional speed constraint to DeLeon’s list, Terrell identifies five aspects of competitive Smash that stretch the five standard meta rules through the addition of competitive play. Terrell (2011b) observes how “metagames are very cultural in that they reflect the trends, discoveries, behaviors, and beliefs of a group of people” but despite forum discussion, tournament videos, and livestreams, the history of the metagame does not leave a mark within the software. There are no footprints in the sand.[50]

While the mechanical, electrical, and algorithmic constraints of Super Smash Bros. as an assemblage of technical media may not change according to how people play, the homebrews, hacks, and modifications of Nintendo games transform the metagame into an explicit game design practice, codifying historical play into bits and bytes. Terrell’s “Project M-etagame” is a cheeky citation of Project M (2011–2015), a community-built, “piracy-free” mod that attempts to rebuild Super Smash Bros. Melee inside the Super Smash Bros. Brawl engine for home console. Terrell (2011c) calls Project M a “Melee-Brawl-hybrid” which means a metagame historian must “take into consideration the development of Melee and Brawl’s metagame to best understand the start of Project M’s development.” However, the reverse is also true. Project M also preserves the history of the metagame within the patch updates and change logs stored on the Smash Boards forums and in each version of the software itself.[51] Play and practice converge in Project M, a digital artifact that captures the metagame in each software update like insects trapped in amber. From a corporate game about games to the glitchy game hidden within the game to the competitive game around the game to Project M, the hands of players move from manipulating characters, to discovering mechanics, to organizing tournaments, to designing a videogame.

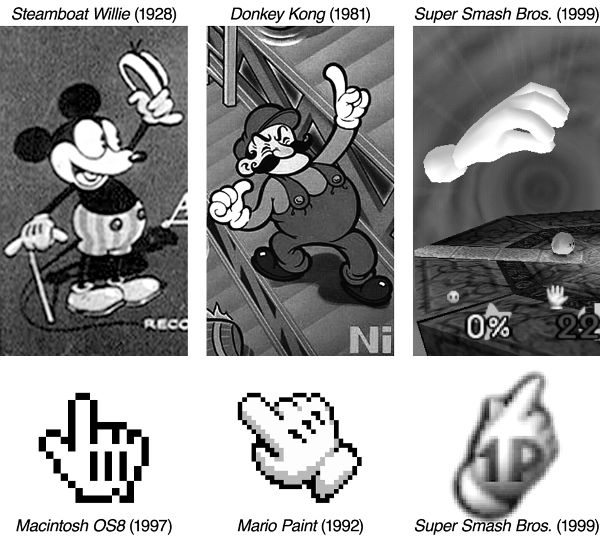

Super Smash Bros. begins and ends with its own “Master Hand.” The disembodied white glove with a mind of its own first appears in the opening cutscene of the original Super Smash Bros. before serving as a cursor icon within the game’s graphic user interface (GUI). Throughout the series, Master Hand returns as the final challenger that must be defeated to complete the single-player campaign. Circling an Edenic mise-en-scène of a child’s suburban bedroom, Master Hand begins Smash Bros. by reaching into a toy box to retrieve one of eight different dolls—miniature versions of Nintendo’s intellectual property represented as playthings for the idle hands of a global corporation.[52] Dumping a limp Mario, Link, Kirby, etc. onto the nearby desk, a snap of the fingers brings the characters to life as the books, lamp, and windowsill morph into a scene from the Mushroom Kingdom. Ready? Go! Representing Sakurai, Iwata, and the game’s other creators at HAL Laboratory and Nintendo, Master Hand’s magic recalls the long tradition of the hand of the animator that appears at the birth of film itself.[53] Whereas this first, cinematic Master Hand enacts a metaleptic leap between Super Smash Bros.’ diegesis and its designers, control is soon shifted to the interactive hand of the player.

Having breathed life into Nintendo’s action figures, the hand of the animator becomes animated in Super Smash Bros.’ character selection menu. While the metaleptic Master Hand in the opening cutscene recalls classic cinematic tropes, the metonymic Master Hand in the GUI recalls Susan Kare’s “clicker” icon that first appeared in Apple’s HyperCard software in 1987. As with Mario Paint (1992) and Mario 64 (1996), players manipulate Super Smash Bros.’ menus by guiding a miniature version of Mario’s hand, the Master Hand, to point, pinch, and place data in the form of a cursor icon. While the hand of the animator becomes the hand of the player, the darted glove included in Nintendo’s games (and eventually replacing Kare’s original icons in Apple’s operating systems) is itself an iconic figure in the history of animation. Both Mario and the Macintosh’s white, right-hand glove not only intentionally signify Mickey Mouse but also, unintentionally, the much longer racial history of cartoons (see Figure 1.7).