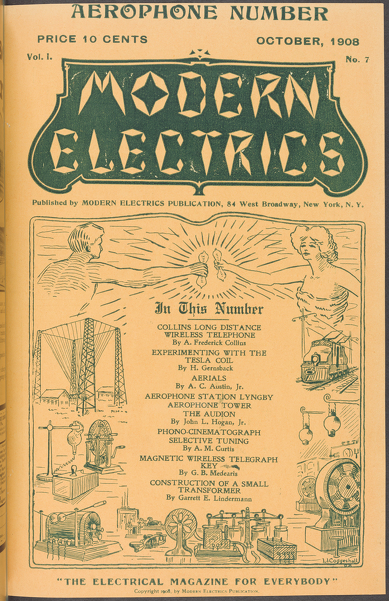

The Aerophone Number

Modern Electrics, vol. 1 no. 7, October 1908

It affords the Editor great pleasure to present to his readers herewith the first “Aerophone” number.

As is most likely the case a good many readers were surprised at this title, and an explanation is due.

We have grown so accustomed to the word “telephone” that we use it over and over without being conscious that it really means “far voice.” You will say: “I shall telephone you,” but nobody would think to say: “I shall far-voice you.”

A short word has long been needed to express what is known now under name of “wireless telephone.”

It sounds decidedly odd to say: “I shall wireless telephone you,” or “I shall telephone you wirelessly.”

The word “radio-telephone” expresses the idea a good deal better, but still it sounds strange if we say: “I shall radio-telephone you.” Better would be the shorter word “radiophone.” But it does not seem to sound quite right when we say: “I shall radiophone you,” or: “I have received a radiophonic message.”[1]

Somehow or other it sounds harsh. The Editor suggests the word “Aerophone,” which not alone sounds well, and is easily remembered, but expresses the idea correctly. Translated it means: “air-voice.” In other words, talking through the air, while telephony stands for talking over the wire. The word radiophone does not convey the idea that no wire is used, while Aerophone does.

The words, Aerophone, Aerophony, Aerophonic, sound good, and are to the point.

As will be seen by perusing this issue, the new word has been used almost throughout and the Editor shall continue to use it until a better one is found, or until another word is universally adopted.

The Editor shall furthermore be grateful if every reader would have the kindness to drop him a postal card stating which word he desires to become universal.

Results will be published in next issue.

Modern Electrics claiming several records, with this issue adds a new one to its list. No magazine heretofore issued an “Aerophone Number,” or a “Wireless Telephone Number,” the honor belonging entirely to Modern Electrics, leading, as usual.

Note

1. The medium that Gernsback attempts to name here is best understood as an early conceptualization of radio. While the voice had been transmitted wirelessly as early as 1900, most notably by the Canadian inventor Reginald Fessenden using an electrolytic detector (see The Radioson Detector in this book for more), a reliable means for accurately sending sound, voice, and music signals was still a ways off. Because the broadcast model of radio we are familiar with today had yet to be imagined, most projections of wireless voice transmission involved a point-to-point model resembling a telephone conversation.

“Aerophone” never took off as a name, and other contenders like “radiophone” and “wireless telephone” were eventually simplified to “wireless.” While the term “radio” replaced all of these by the 1920s, today there is a resurgence in the use of “wireless” thanks to new applications of the technology in WiFi, near field communication, Bluetooth, and cellular systems like GSM and CDMA. But it is interesting to note how the cultural form of broadcast radio—only one application of wireless, or the physical transmission of electromagnetic signals—was for a time synonymous with the general technology.